- The factors that need to be considered when choosing a new home for a telescope

- What it’s like to spend time on location testing a potential telescope site

- Why it can take up to ten years to choose a site for a new observatory

Q. Firstly, can you tell us a bit more about your role here at ESO?

Marc Sarazin (MS): I was hired back in the eighties to help choose a site for the ambitious Very Large Telescope (VLT), and I still work in telescope site selection today! In reality this means working with other staff and local contractors to decide on the best place for a telescope to be located. We gather lots of information about a site before the final site selection committee — which is made up of astronomers representing the scientific communities within ESO’s Member States — makes a final decision about which one is best.

Julio Navarrete (JN): And I started at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile two years after Marc started at Headquarters. I worked on site testing full time until the VLT began operating, then moved to science operation with 15% of my time dedicated to site monitoring. Before I joined ESO I was working in oil exploration; I completely changed perspective, from looking down to looking up at the sky!

Q. What would you say are the most important criteria to consider when choosing on an astronomical observing site?

MS: There are so many aspects to consider. Some of these, like clouds, wind, and altitude, impact the science a telescope is able to carry out. We constantly monitor the turbulence in the air above the observatories, because we want the air to be as still as possible, to minimise the blurring of light from the Universe as it travels through Earth’s atmosphere. But we also need to consider other more practical factors like cultural issues, building and maintenance costs, and ease of access to the site.

Then there’s geology. It’s easier and cheaper to build on solid rock than sand, for example, and telescopes are very sensitive to earthquakes, so an earthquake-free zone is a bonus. Low temperatures can also pose problems because they cause the lubricant oil in telescopes to freeze. And we want to avoid dusty areas because dust landing on the mirrors can damage reflective coatings. With so many factors to consider, it takes a very long time to test and select a site!

JN: We are also careful not to disturb animal populations too much, so ecological studies are carried out by independent institutes. For instance, when choosing a site for the ELT, we discovered that some desert mice lived on the preferred site. Fortunately there weren’t too many, so we didn’t consider it too detrimental.

The important thing to note is that it’s impossible to find a perfect location with no problems at all. We always need to weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of each site, and finally work towards a compromise.

Q. Can you walk us through the process of testing a site?

MS: We start by using satellite observations to identify many large areas that could be suitable for a site, scientifically speaking. We eliminate some for political or safety reasons, and are typically left with three or four. Then we look for specific candidate sites within each area, for example dry summits with low levels of light pollution. And nowadays, as most people do before they go on holiday, we also tend to have a look around on Google maps before visiting the sites in person.

For example, when choosing a site for the VLT, in South America we narrowed the choice down to Argentina and Chile. Both countries have lots of summits — just beautiful! — but there is also a lot of mining, so we needed to find somewhere far from the mines to avoid vibrations and dust. We set up dedicated robotic stations at sites across both countries, which took measurements for several years before we could make a decision. For the VLT, we also tested Gamsberg in the Namib Desert and checked sky conditions at Reunion Island.

JN: Whilst site testing for the VLT, I had to stay onsite in a caravan with just a driver and a cook for several months at a time! This was during the eighties, when we didn’t have such independent robotic equipment, so it took more human effort to make measurements at a site. I was in charge of operating the testing instrument, diagnosing and repairing failures, and cleaning the dishes after meals.

For the VLT, it took seven years in total to select Cerro Paranal to be its future home, with about five of these involving site testing. Testing for this long ensures that we are confident about site conditions, and are sure that we are not just testing the site in a fluke year with particularly superb conditions. But Cerro Paranal is truly excellent, with very little rain or cloud cover, wonderful conditions to carry out science, and virtually no light pollution.

Q. And more recently you were both involved in selecting a site for ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT). Was it difficult to choose a home for the world’s “largest eye on the sky”?

MS: Even though the ELT is huge, choosing a site for it was actually no more difficult than for the VLT, because the ELT is just one single telescope whereas the VLT is made up of four large Unit Telescopes.

For the ELT we considered sites in the Canary Islands, Morocco, Argentina and Chile. One committee was set up to analyse the scientific quality of each site based on data we provided, as well as that provided by other site testing groups using the same equipment. Then another committee had the arguably more difficult job of looking into the socio-economic nature of each site, for example political issues, ease of access and cost of construction.

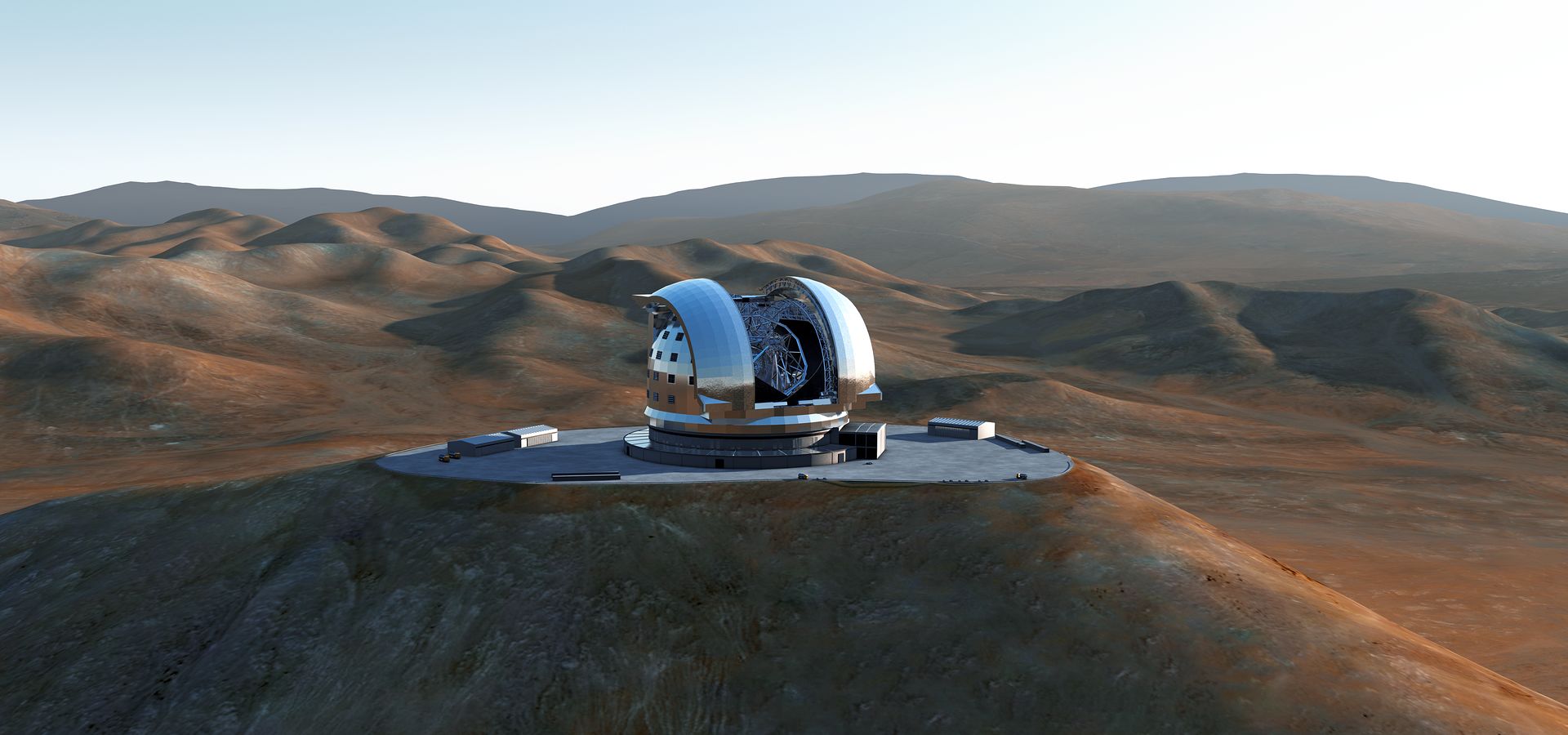

JN: But before we had come to a final decision, we had a stroke of luck. The American Thirty Metre Telescope (TMT) was due to be built on top of a mountain called Cerro Armazones, very close to the VLT. We had actually previously considered this site as a potential for the VLT. Cerro Armazones was a wonderful site and would have been an excellent location for the TMT, but in 2009 it was decided that it would make more sense to build the telescope in the US state of Hawaii. This left Cerro Armazones thoroughly tested and now wide open.

This mountaintop outshone all the other sites we had been looking at, so ESO snapped up the opportunity and decided to build the ELT there. Not only are the weather conditions excellent, but the proximity to the VLT means that a lot of infrastructure, for example roads and a hotel, already existed that we would have otherwise had to build. ESO also already had various agreements in place with the Chilean government, so that simplified things a lot!

Q. Do you continue to monitor a site whilst science operations are ongoing?

MS: Yes, we continue to monitor the “astroclimate” even when the telescopes are built and operating, using an on-site meteorological station. We do this so that astronomers can capture the best possible images, to understand the performance of the instruments and to better-plan observations. For example if we monitor a site for several years, we can predict which months are better from a scientific point of view. We can plan difficult observations during those periods, and schedule maintenance during the worst months.

And because of climate change, some parts of the world are changing faster than others. The stability of a telescope site is really important, so we do look at how conditions change over a longer period of time. We know that the Atacama Desert, for example, has been a desert for hundreds of years, but there are cycles in the clouds. When we were first monitoring the site, about 15% of nights were cloudy. As time went on, this percentage steadily increased, and now it’s steadily decreasing again. This is a cycle that lasts about 30 years.

Q. Do you think astronomical sites will be chosen in the same way in the future, or will technological advances change the process?

MS: There was already a huge difference between choosing a site for the VLT and choosing one for the ELT. For the VLT we were using paper satellite photographs to study cloud cover, whereas for the ELT we had big databases based on meteorological models. We now have meteorological data with a resolution of just a couple of kilometres, compared to 40 kilometres in the eighties.

We also now have information about the historical weather at a site, meaning that we don’t need to spend months or years checking the weather conditions. We do, of course, still need to investigate geology, whether we would be disturbing animal populations, and more practical issues like how easy it will actually be to build a telescope there.

JN: But overall, now we spend a lot more time monitoring sites remotely from our offices than actually staying on the site itself. This is sad for me, because my favourite part of my job is to be out in the field, even if that means being the designated washer-upper!

Numbers in this article

| 4 | Number of Unit Telescopes that make up the VLT |

| 7 | Number of years it took to select a site for the VLT |

| 15 | Percentage of time that Julio spends on site testing |

| 15 | Percentage of cloudy nights in the Atacama Desert when monitoring began in the eighties |

| 30 | Cycle of varying cloud conditions in the Atacama Desert (in years) |

| 1980s | Decade that both Marc and Julio started working at ESO |

| 2009 | Year that it was decided to build the TMT in the US state of Hawaii — one year later, it was decided to build the ELT on Cerro Armazones |

| 2010 | Year that it was decided to build the ELT on Cerro Armazones |

Biography Marc Sarazin and Julio Navarrete

Marc Sarazin is an Applied Physicist at ESO. He is responsible for monitoring the quality of the existing ESO sites, developing new instrumentation for monitoring and understanding the "seeing"/astroclimate and monitoring the impact of long-term trends in environmental conditions on image quality. Marc has developed and maintains operational forecasting tools which contribute to the excellence of ESO Science Products. He is also involved in the establishment of future sites for ESO facilities, leading the site survey activities for both the VLT and the ELT projects.

Julio Navarrete is an electronic engineer who joined ESO in 1987 to work on the site testing for the VLT project. After the start of VLT operations in 1998, Julio moved to the Paranal science operations department, where he is still working on as operations specialist, operating the VLT units and their associated instruments (night shift) and data quality control (day shifts). From 2005 up until selection of the ELT, Julio spent 75% of his time on science operations tasks and 25% of his time on ELT site testing tasks. When the ELT site was chosen, his time dedicated to ELT site characterisation tasks decreased to 15%, with 85% remaining to be science operations.