Boy Scouts Into The Unknown

Jan Doornenbal on ESO’s pioneering site testing in South Africa

- How early astronomers decided where to locate ESO’s observatories

- What makes a good telescope site

- What it was like living in the South African desert

Q: How did you first find out about the opportunity to help with site testing?

A: It was 1960, and for six years I had been working at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) as a mechanical apprentice by day and going to school four evenings per week. I’d also been active as a Boy Scout for 13 years, and seemingly just at the right moment, an advertisement appeared in the monthly scout magazine.

The ad was sent by the Dutch Organisation for Pure Scientific Research (or the Dutch ZWO), and they were looking for youngsters with a pioneering spirit to participate in an astronomical site testing expedition in South Africa for six months.

After expressing interest, I went along to a slideshow in Amsterdam conducted by Dr Andre Müller, who had been working for some time in South Africa looking for suitable sites. He gave us first-hand information about what it was like to live and work there.

Afterwards, I sent a letter to ZWO expressing my interest to continue. I felt it was time for a break after six years of working and studying — especially after riding eight kilometres to school and back four times a week, in sunshine, rain, storm, snow and ice. I was ready for a change.

Q: Did you already have an interest in astronomy?

A: Astronomy had not come into my mind at that time. I was interested in mechanics, and I wanted to be involved in designing, developing and building unique scientific instruments — from the beginning to the end. I was also interested in amateur radio communications (building shortwave receivers) and aviation (scale gliders in an aviation club). Looking back now, it seems impossible to do all this at the same time, but I never watched much TV!

Q: How did you travel to South Africa?

A: Once I was chosen, things moved rapidly. It was December and the trip left at the beginning of February. I received boat tickets — I had hoped to fly by Kilimanjaro with its eternal snow in the middle of the African continent, but flying was still very expensive!

We went from Hoek van Holland by ferry to Harwich in the UK. That was where I met Albert Bosker for the first time — another Dutch youngster who became a good friend of mine. From there we went to London to stay overnight, then on by train to the seaport of Southampton. We took the passenger ship RMS Pretoria Castle on the Union Castle Line to Cape Town. Everything that was happening was very different and so exciting that there was not much time for thinking about what we had left behind at home.

Q: How did you test different sites?

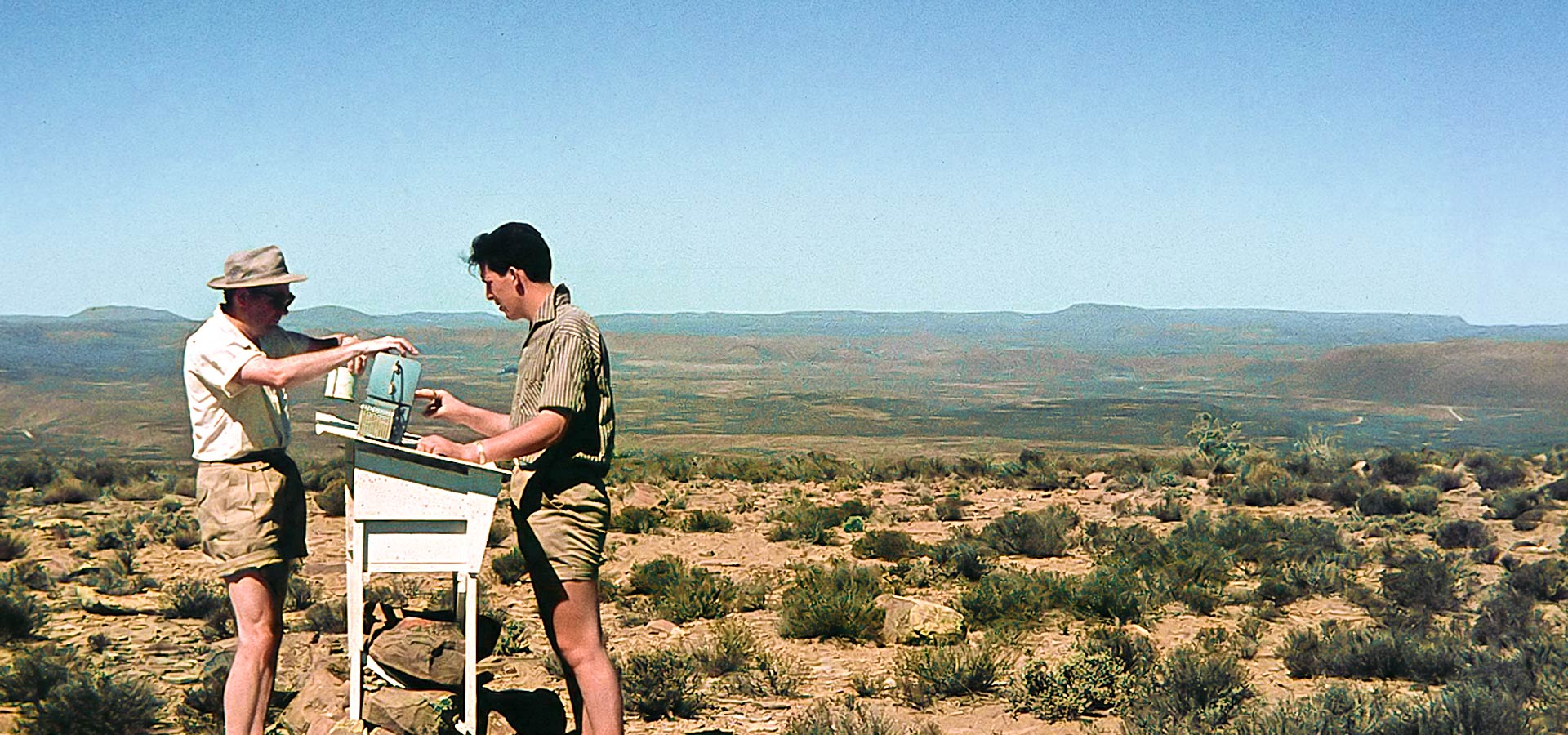

A: When I first arrived in South Africa, I, of course, had no idea what made a place suitable for an astronomical observatory. But after time, talking with several co-workers and astronomers on cloudy nights, I began to understand. Astronomers were looking for a place with perfect meteorological conditions, to get the best possible results from these telescopes. Namely, they were looking for places with a constant flow of air without disturbances. The landscape shape around the site is also very important, as is the thickness of the atmosphere above the site — the higher up the site, the thinner the atmosphere, and the better for observing.

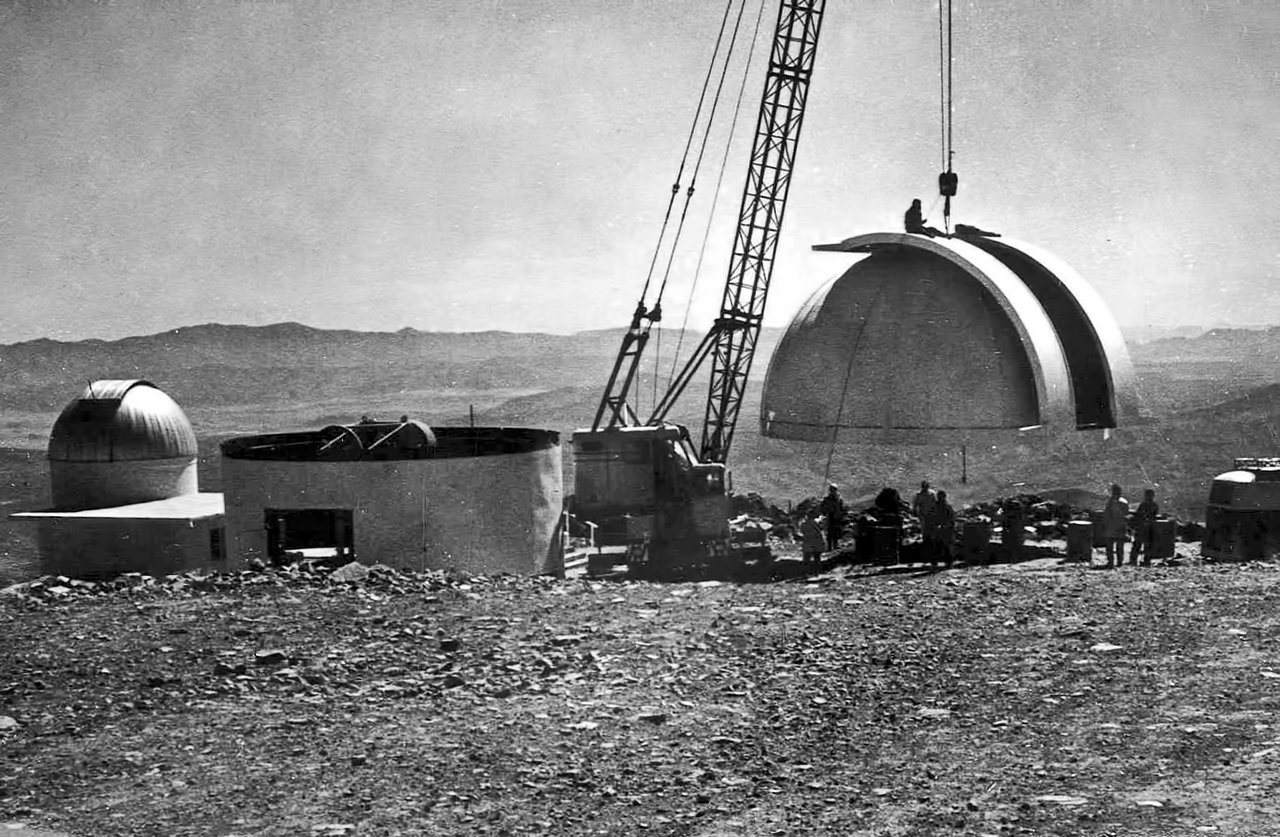

Four promising sites were preselected: Table Mountain, Rockdale Mountain, Flathill and Zeekoegat, all fairly close to each other. They were in a semi-desert area with the name The Great Karoo in the Cape Province, which has an average elevation of about 1000 metres. Each of these sites then had to be thoroughly tested.

Our site testing group consisted of three teams of two youngsters each, of German, Dutch, Swedish and South African nationalities. Our task was to measure the seeing, which indicates how good a site is, for 24 nights in a row, from sunset to sunrise. We had six days off around the Full Moon. We had to randomly observe the twinkling of 10 different stars in all directions — half an hour of observing, then half an hour off. To observe the seeing conditions, we used a primitive Danjon telescope that consisted of a wooden box with a 25-cm mirror, a prism and an eyepiece. We also had to note temperature, wind direction and wind speed every hour at night, and as long we were awake during the day. In the last year of our stay — we stayed for two years longer than expected! — we also had to make measurements using the Sun, every hour during the day.

Then on the last night of each 24-day period, all the groups came together at Flathill and compared our measurements.

Q: What was it like to live in South Africa?

A: I was permanently stationed in an old farmhouse, where there was fresh drinking water but no electricity. However, we managed with gas lamps instead of electric lights and the fridge was run on paraffin. We each had our own room, and a local cook made our meals. Once a week we went to the supermarket in Beaufort West to buy the necessary groceries.

At night on the mountain, we used one of the first transistorised reel tape recorders to listen to some music. Cassette decks were yet to come! To listen to the radio, we had a state-of-the-art portable shortwave receiver. Radio Portugal Mozambique played very good music at night!

To make a phone call from the farmhouse was not a simple operation — it could take hours to establish a connection, and sometimes it was not possible because all was done by hand, switchboard to switchboard in Africa. This meant that writing letters by airmail was the most useful way to communicate with friends and family, which took 7 to 10 days each way.

Q: Why didn’t ESO end up building its telescopes in South Africa?

A: While ESO was busy in South Africa, similar site testing was going on in Chile for American observatories. ESO soon became aware of Chile’s favourable conditions for astronomy — everyone was suddenly and enthusiastically talking about looking there too. It was suggested that one of our main observers should go to Chile to compare with the American results.

I believe that the reason to move to Chile had both practical and political motivations. Not only were site testing results in Chile better than those in South Africa, but also in those years South Africa was widely criticised for its apartheid politics. It was said that the government of one of the important participating countries opposed the decision and would stop paying for the participation in a future astronomical observatory in South Africa.

So one of the South African youngsters by the name of Paul McSharry travelled to Chile as a site testing observer, together with Andre Müller, and my period in South Africa came to an end after two marvellous years. Albert Bosker and I went home by boat again, the same way we had come.

By 1964, it had been decided to build ESO’s first observatory in Chile, at La Silla.

Q: What did you do once you were home?

A: For me, there was a gap of three years between my South African experience and my start in Chile. During those years I worked at the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. Adriaan Blaauw was Director here — a Dutch astronomer who would later become ESO’s second Director General.

I was designing and building the first astronomical instrument made especially for ESO. All other instruments and telescopes that ESO used in the beginning came from other observatories in France and South Africa, adapted for La Silla’s geography. But we were working on a photometer designed specifically for a one-meter telescope to be delivered to ESO.

It was not easy to make in those years because optics were difficult to find. In the end, we used parts from military dump stores to get everything together. I made the technical drawings and most of the mechanical parts, and also had to get acquainted with the assembly and adjusting of the telescope in order to later put parts together on La Silla in Chile.

Q: What was it like when you arrived in Chile?

A: When I arrived, construction of the 20 km road from the base camp to the mountaintop of La Silla and other infrastructure had started. We stayed in an older camp where the horses and mules — used to transport supplies up the mountain — were kept. A small wooden shed became my temporary home. In order to learn Spanish quickly, I spent two weeks working with local craftsmen — such as carpenters and gasfitters — who were constructing the kitchen and dining room for the personnel.

Andre Müller was already there and had identified good locations on top of the mountains for the telescopes on their way from Europe and South Africa. I and German astronomer Hans Schuster went up to help him to make the precise measurements that determined the exact positions for the telescopes. For about two months we were living in a small camp on the mountain with two shacks, one for sleeping and one for cooking and eating. This was the first fixed camp on La Silla.

Then the first car arrived on the top of La Silla, and then the bulldozers. Afterwards, things started to change very quickly, and big improvements in living conditions occurred.

Later in 1966, the ESO 1-metre telescope was the first telescope at La Silla to become operational.

Q: How long did you stay at La Silla?

A: I stayed for five years. By the time I left ESO in 1970, I had been working for the organisation for ten years. In this span of time, things had changed a lot. When more telescopes became available at La Silla, the number of people on the site grew rapidly. Better accommodation and facilities were also built and I like to think of it as another world appearing at La Silla. I loved the irregular life during those years; plus in 1967 I had married the Chilean love of my life.

Then in 1969, I heard from the Kapteyn laboratory in Groningen that a new branch had started — they were taking part in the Dutch IR Astronomical Satellite, working together with factories like Fokker and Hollandse Signaal: well-known institutions for precision mechanical instruments. This meant working with new materials, making things function at very low temperatures, and so on, but all in the field of astronomy, and so I decided to return to the Netherlands to work again at Kapteyn.

Later, in the 1980s, I also worked for a Dutch astronomical group that was participating in a joint observatory on the island of La Palma, in the Canary Islands of Spain. I lived there for 25 years — but when I retired, my wife and I returned to Chile in 2007.

Looking back on all of this, I think it has been a fantastic life — and I am realising now that it has been a very out-of-the-ordinary one. Of course, in life one finds ups and downs, but on the whole the ups prevailed by far.

Numbers in this article

|

2.5 |

The number of years that Jan spent in South Africa |

|

7–10 |

The days it took for letters to travel from South Africa to Europe |

| 21 | Jan’s age when he was selected to help with ESO site testing |

|

24 |

Astronomers and their assistants measured the seeing of a site for 24 nights in a row, from sunset to sunrise. |

|

1961 |

The year Jan first set out for South Africa |

| 1966 | The year the first telescope became operation at ESO’s brand new La Silla Observatory in Chile |

Links

- ESO’s La Silla Observatory

- Learn more about the site selection on the ESOcast special episode "Going South"

- Read about the ESO 1-metre telescope

- Read more about ESO’s early history in The Messenger

Biography Jan Doornenbal

Dutch-born Jan Doornenbal began his career at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute as a mechanical apprentice, and in 1960 was selected to travel to South Africa to aid in site testing for ESO telescopes. Later, after working on an ESO instrument at the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute in the Netherlands, Doornenbal lived in Chile for five years to aid in building ESO’s first telescopes at La Silla. Doornenbal returned again to Holland for work and later moved to the Canary Islands to build a new observatory, and lived here for 25 years. Upon retirement, he returned to Chile with his wife.