- How certain human activities endanger the night sky

- What is the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and ESO’s role in it

- How viewing astronomy as a space activity can help us protect the night sky

An endangered treasure

There are many things in life we take for granted without realising they might not be there forever. The starry night sky and ground-based astronomy are two of them. Like for the last survivors of a disappearing species, we witness the relentless shrinking of the natural habitat from where we can admire them.

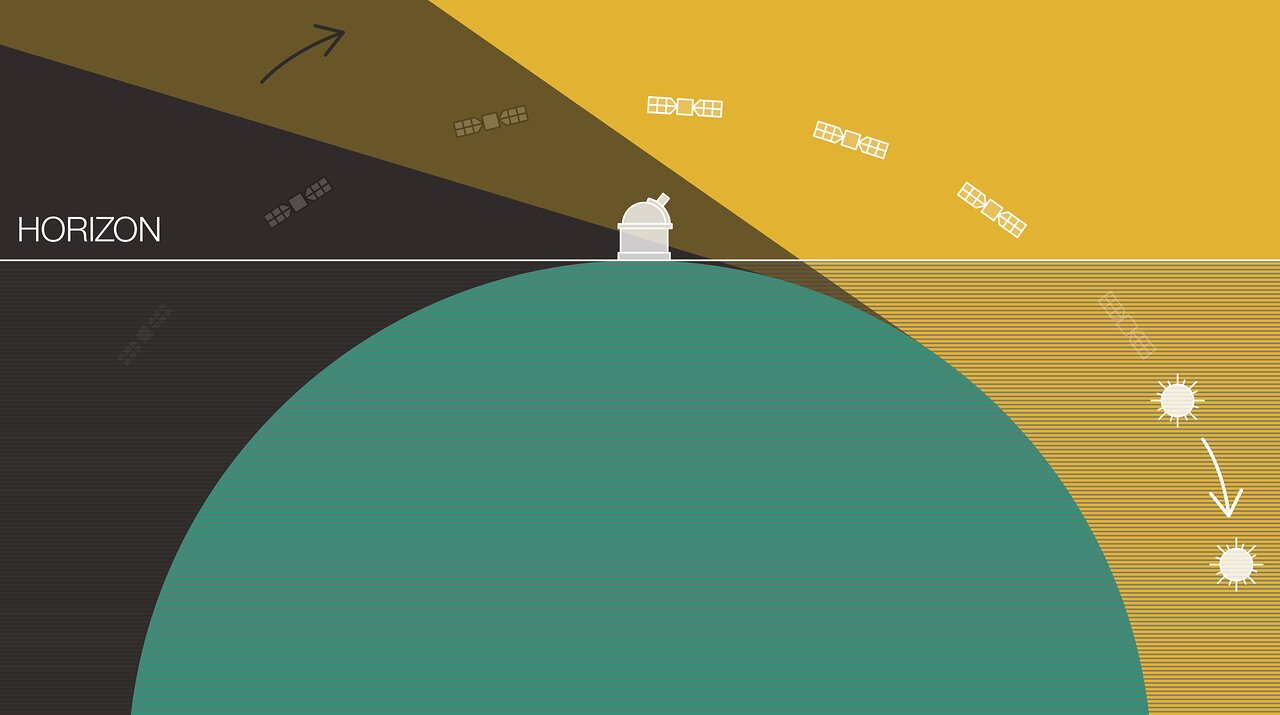

The progressive loss of the starry sky and the increasing difficulty to perform some astronomical observations from the ground are a self-inflicted wound. Light pollution from our ever expanding cities and low-orbit satellite internet constellations, which can interfere with optical and radio observatories, degrade our view of the cosmos.

“The human degradation of the outer space environment has been a problem since the ‘60s, with the Project West Ford, when a belt of millions of copper wires was to be sent around the Earth to create a global communication system,” says Giuliana Rotola, in her role as Space Law and Policy Project Group Co-lead at the Space Generation Advisory Council. “In space there is freedom of access, so every activity is in principle acceptable. It is different from airspace, as there is no jurisdiction or sovereignty, and we need to find the balance between the freedom of access to space and the exploration of space.”

It is paradoxical that ground-based astronomy is experiencing an unprecedented era of discoveries and technological development and, at the same time, it is threatened as never before. Space telescopes are less affected by these issues, but they only complement ground-based telescopes and can’t fully replace them. [1] Fortunately, the astronomical community is already taking measures to preserve the starry night, supporting light pollution control and working with satellite companies to mitigate the effects of their constellations. But how can we protect the sky at a more fundamental level?

United for the stars

One successful attempt to raise awareness about the importance of the night sky and astronomy was the effort by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), with support from ESO among others, to have the United Nations (UN) recognise 2009 as the International Year of Astronomy. The initiative celebrated the 400th anniversary of Galileo pointing the telescope to the sky for the first time — a simple gesture that changed humanity forever.

But not all attempts have been successful. The request to UNESCO made by the IAU to have the night sky recognised and hence protected as a world heritage proved to be unfeasible, for only Earth-based sites can be labelled as world heritages.

Andrew Williams at the June 2019 session of COPUOS.

Credit: A. Williams

Giuliana Rotola at the 2019 graduation ceremony of the Master of Space Studies Program of the International Space University.

Credit: G. Rotola

|

Following up on this unsuccessful attempt, in 2017 the IAU, ESO and other organisations decided to make their next move directly at the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS).

“COPUOS is a child of the Cold War,” says Andrew Williams, External Relations Officer at ESO. “After the Sputnik was launched in the 50s, there was this fear that space could become the next zone of conflict between the East and the West. COPUOS started as an ad-hoc committee under the UN General Assembly, but eventually it was set up as a permanent body with the basic mandate to stimulate international cooperation in the peaceful uses of outer space.”

Together with other organisations, such as the IAU, the European Space Agency and the European Union, ESO is a permanent observer at COPUOS. “As a permanent observer, you do not have the same rights as a member state, so you can’t raise an agenda item and you can’t vote,” explains Andrew, who represents ESO at COPUOS. “But for any kind of important space organisation it's critical to be a member of COPUOS because that's where the discussion about international law in space happens. By being there, we can advocate for astronomy to policy makers.”

The new proposal by the IAU made at COPUOS was successful, leading to the “Dark and quiet skies” project. The initiative will culminate in a conference looking at the protection of the night sky, organised by the IAU, the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UN OOSA) and the host country Spain in La Palma in October 2021. The event follows up on a previous conference organised in La Palma in 2017, on the 10th anniversary of the Starlight Declaration in Defence of the Night Sky and the Right to Starlight. Its main outcome will be a set of guidelines for governments and companies on how to reduce the detrimental impact of modern technology on astronomy, a document which will then be presented to the world governments at COPUOS.

The “Dark and quiet skies” project is a very promising initiative, but Andrew felt that we should move beyond guidelines and establish a legal framework recognised by international governments. And one day he had an idea: to ensure stronger protection, we should look at ground-based astronomy as a way to explore space.

The key: astronomy as a space activity

“Astronomy is a space activity in my view,” says Andrew, “and I would say it’s currently the main way we get to explore space, because you can't go and visit every single planet and every single minor body in the solar system: the main way that this is done is through astronomical telescopes.”

But there is much more to astronomy as a space activity, as Andrew summarised in a dedicated post. “Astronomy supports many critical functions of space activities, from tracking spacecraft to providing critical scientific observations to support space missions. And in terms of capacity building, with data archives, it is an important way for developing countries to experience space, often acting as a gateway to develop a national space capability.”

And last but not least, “with the International Asteroid Warning Network, astronomers can warn us about one of the few natural disasters that we can actually do something about. For example, we are using ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile for 30 hours a semester to track threatening asteroids and refine their orbits,” concludes Andrew.

Andrew’s idea was that, by looking at astronomy as a space activity, it could be possible to protect it under the Outer Space Treaty, the document governing the use of outer space developed by COPUOS and adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1967.

"The Outer Space Treaty is kind of a constitution for space activities,” explains Giuliana. “It provides the fundamental principles that are regulating the use and exploration of outer space. In particular, that everyone should be able to explore and investigate it, and that this should happen for the benefit and interest of all countries. And astronomy, even when ground-based, is fundamental for the exploration and use of outer space and enables other space activities, and so it should fall under its scope and be protected by its principles.”

Now that the idea was there, what was missing was a formalised set of arguments to convey it. To tackle this, Giuliana joined forces with Andrew, spending some months at ESO to bring their different backgrounds together: Andrew’s knowledge of astronomy and Giuliana’s expertise on space law.

“It is a problem that people with different compartmental knowledge often do not get together, so lawyers work with lawyers and astronomers work with astronomers,” says Giuliana. “But an interdisciplinary perspective is very important, because you cannot address the problem of the protection of astronomy just by knowing astronomy, you need to know the legal framework, and you cannot do it just by knowing the legal framework, you need to understand how space works.”

And hard work paid off, resulting in the publication of a dedicated paper outlining the proposal and the supporting arguments. “It's probably not going to result in any kind of immediate changes, but I like to think of it as a seed, that by going to COPUOS and talking about this will grow in many different people’s minds,” says Andrew.

A starless humanity?

Andrew and Giuliana’s story is a new tile in the puzzle of the preservation of the night sky and astronomy. And the risk we are facing naturally leads to the question of how a humanity without astronomy would be.

“It's hard to imagine because we've never experienced it,” says Andrew. “But we would probably have a very, very different perspective on life and our place in the world. And then there’s the search for life: in the same way the Copernican and Galilean revolution was a massive shift in culture, to know that there's life out there somewhere would represent one of the greatest changes in humanity.”

“On one side, astronomy can prevent the end of our civilization by warning us about dangerous asteroids, and on the other side it can support its flourishing beyond Earth,” adds Giuliana. “Moreover, the night sky connects humanity as it is the same for different populations. Without it, we would be even more divided.”

Notes

[1] Space telescopes have certain advantages over ground-based ones, such as being unaffected by atmospheric turbulence or light pollution, and observing at certain wavelengths blocked by the atmosphere. But they are not without problems: they are expensive, they impose tight constraints on the size and complexity of the instruments onboard them, and can’t be easily fixed or upgraded.

Links

Biography Giulio Mazzolo

Giulio Mazzolo is a science journalism intern at ESO. Before starting a career in science communication, he completed a PhD in astrophysics from the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Hannover (Germany) and has been a member of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration.