- What happens during a solar eclipse

- About the solar eclipse that was recently visible from ESO’s La Silla Observatory

- Some historical solar eclipse legends

- Important scientific discoveries made by observing solar eclipses

Just about 2000 years ago humans came to understand that a solar eclipse occurs when the orbit of the Moon causes it to pass exactly between the imaginary line connecting Earth and the Sun. When this happens the Moon blocks the light from the Sun, casting a shadow onto the Earth, which moves across Earth’s surface as it rotates.

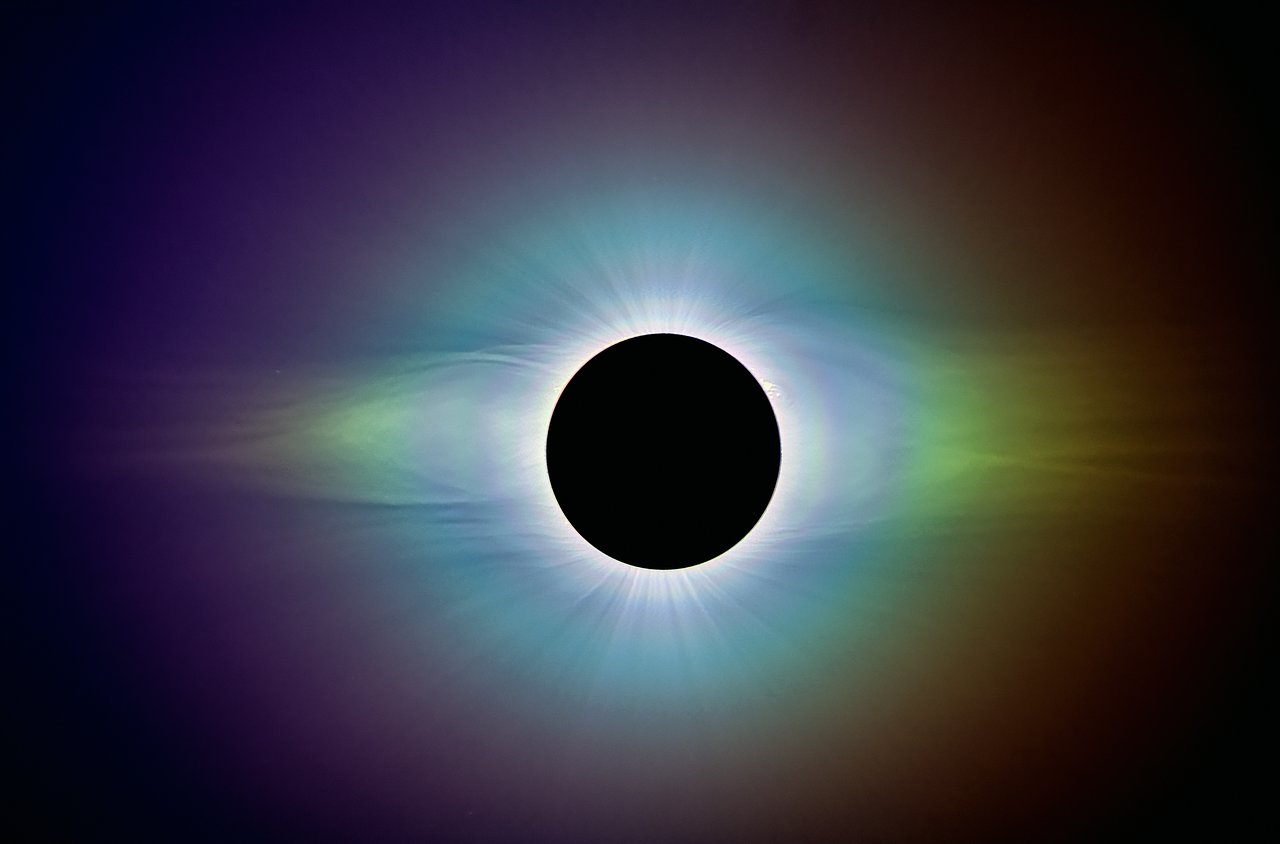

Solar eclipse expert and ESO photo ambassador Petr Horálek explains, “A total eclipse happens because although the Sun is about 400 times further from the Earth than the Moon, its diameter is 400 times larger. This means they appear the same size in the sky so the Sun is almost perfectly blocked by the Moon. The really amazing thing about this is that a total solar eclipse gives us the chance to see the Sun’s corona — the outer layer of its impressive atmosphere. And if that wasn’t enough, there are many breathtaking phenomena to be seen in the moments before and after the Moon completely blocks the Sun”.

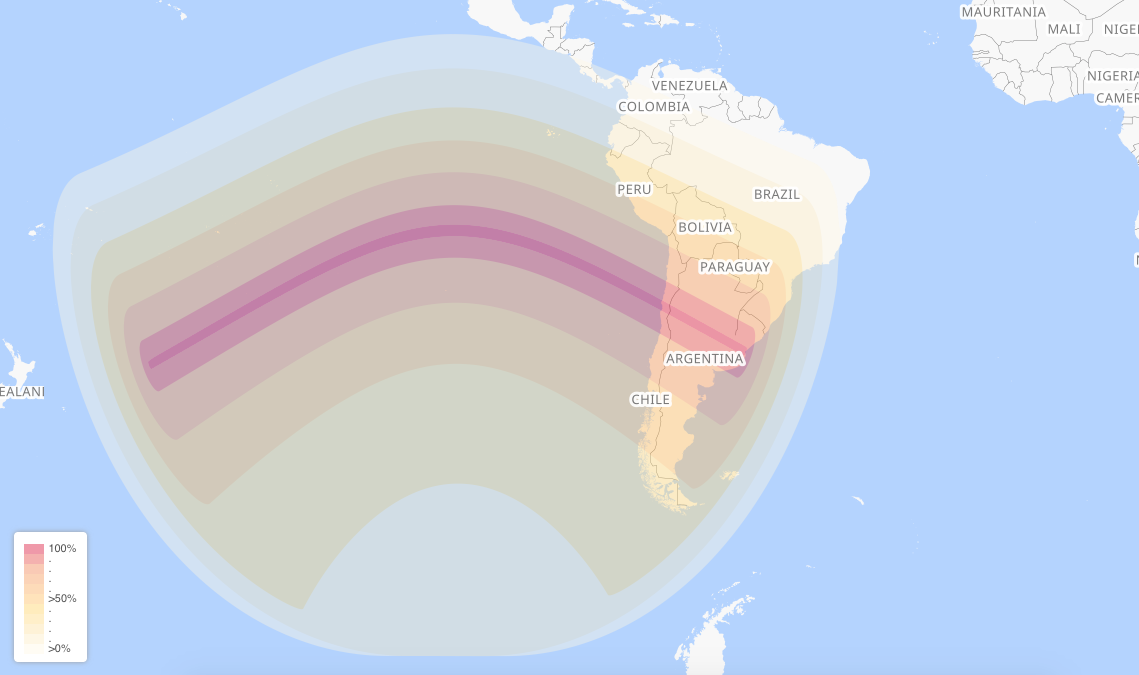

The recent solar eclipse at La Silla Observatory lasted more than two hours, with the Sun being completely covered by the Moon for almost two minutes. Over 1000 visitors travelled to La Silla from around the world hoping to get a glimpse of the spectacle. Skies were clear, giving astronomers the opportunity to use the observatory’s world-class telescopes to observe the eclipse for outreach and science purposes, following a long tradition of taking advantage of eclipses for scientific research.

The recent eclipse inspired awe and wonder in all who were lucky enough to see it, but before the phenomenon was well-understood, eclipses were mysterious and often terrifying events. “People are scared of what they don’t understand, and what could be more confusing and frightful than suddenly being shrouded in darkness,” Petr says.

The earliest eclipses were documented on clay tablets and cave walls, with the very first written record coming from China in 2137 BCE. According to traditional astrological theories, the Sun was the symbol of the Chinese Emperor and so eclipses in China stood as imperial warnings.

Petr explains further: “In Chinese culture it was believed that eclipses were caused by a hungry dragon devouring the Sun. The record from 2137 BCE describes two royal astronomers, Chi and Ho, who had not warned others about the eclipse and were too drunk to fulfil their task of beating a drum to scare away the dragon”.

It wasn’t until almost 1500 years later that the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus accurately predicted a solar eclipse, according to ancient Greek historian Herodotus. If Herodotus's account is to be believed, the Eclipse of Thales is the earliest recorded that had been foreseen in advance, even though eclipses were still not understood at the time. How exactly Thales predicted the eclipse remains uncertain it is possible that he knew about the periodicities of eclipses, that he was able to calculate it or that he just made a lucky guess! Horálek explains: “Nowadays it is easy to predict future solar eclipses. They follow a strict periodicity and can be predicted with mathematical calculations that consider the position of the Moon in relation to the Sun. Astronomers can do it for thousands of years into the future!”.

Running these calculations in reverse, many historians believe that the Eclipse of Thales was the solar eclipse of 28 May, 585 BCE. Interpreted by Herodotus as an omen, it interrupted a battle in a long-standing war between the Medes and the Lydians. The fighting stopped immediately, and they agreed to a truce.

Some historical eclipses are still shrouded in mystery. Reports from both Christians and non-Christians of the death of Jesus describe a period of daytime darkness. Some historians believe this could have been caused by a solar eclipse, but bewilderingly, the crucifixion supposedly took place during the Jewish festival of Passover, which is celebrated during a Full Moon. A solar eclipse can only occur during a New Moon. Furthermore, present-day astronomers believe that the only two eclipses to have occurred near the time of the crucifixion were closer to Antarctica and Australia — it seems unlikely that either was visible from Jerusalem!

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that solar eclipse events may have even changed the course of history. Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne, was head of the Carolingian empire when he witnessed a solar eclipse on 5 May 840 CE. According to legend, it terrified him so much that he died shortly afterwards. His three sons then began to dispute his succession. After three years of debate, the quarrel was settled with the Treaty of Verdun. This treaty divided Europe into three large areas which indirectly led to present day France, Germany and Italy.

Three hundred years later in 1133 CE, King Henry I of England died shortly after he observed a solar eclipse. William of Malmesbury wrote in the manuscript Historia Novella that the “hideous darkness” agitated the hearts of men. After the death, a struggle for the throne threw the kingdom into chaos and civil war.

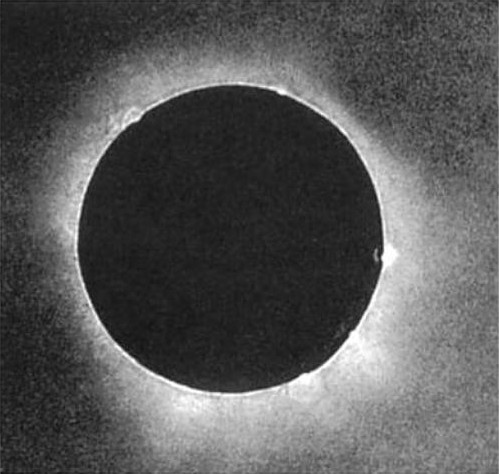

Whilst historical figures were shocked by eclipses, by the seventeenth century physicists began using them to investigate the Sun scientifically. The first accurate and scientifically useful photo of an eclipse was taken in 1851 at the Royal Observatory in Königsberg. To take this photo, daguerreotypist Johann Julius Friedrich Berkowski exposed a copper plate directly to the Sun’s light through a small refracting telescope, capturing an 84-second exposure which for the first time allowed scientists to study the Sun’s corona long after totality had passed.

Eight years later, German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff figured out how to analyse light from the Sun and the stars to deduce their chemical composition. Scientists eagerly awaited the next solar eclipse, which would allow them to study the chemistry of solar prominences. In 1868, the opportunity finally arose. French astronomer Pierre Jules César Janssen camped out in India to watch the Moon pass in front of the Sun, revealing brilliant solar prominences. Like other Sun-gazers that morning, Janssen discovered that the prominences were mostly made of hot hydrogen gas, as was expected. But he also used a spectroscope to discover something intriguing — yellow light was present that didn’t match the wavelength of any known element. Further studies led him to discover that this line was actually produced by Helium, named after “Helios”, the Greek personification of the Sun. And thus Helium was discovered on the Sun before it was discovered on Earth.

When Albert Einstein published his general theory of relativity in 1915, he proposed three critical tests to prove it, one of which was that light should be deflected by a gravitational field. This phenomenon could be investigated by measuring whether light from distant stars is diverted by the gravity of the Sun. Just before the total solar eclipse of 1919, Sir Arthur Eddington took nighttime measurements of the positions of the Kappa Tauri double star in the Hyades cluster. During the eclipse, the Sun crossed Kappa Tauri, and the starlight became visible. Comparison of the stars’ normal positions and the corresponding positions detected during the eclipse showed that light was indeed deflected when it passed close to the Sun. Einstein’s world-changing theory was proved to be correct!

Past eclipses have helped us make many scientific discoveries, but still today mysteries remain that astronomers hope to solve by observing the Sun during future eclipses.

Petr tells us: “In 1869 astronomers William Harkness and Charles August Young captured spectra of the solar corona and found a mysterious new element there. Eventually people discovered that this “new element” was in fact iron that had been ionised 13 times! But this discovery brings with it a bigger mystery; such strong ionisation can only occur in places with temperatures of millions of degrees. The temperature of the corona cannot be this high, so the big question is: where and how does this ionisation occur and how do the ionised elements move to the corona? This is still the greatest coronal mystery”.

Solar tornadoes, vortices of magnetic turbulence that swirl up from the surface, might be to blame. So too may be deeper, magnetic tsunamis within the sun, transferring their heat outward.

“Observations during future eclipses could help settle the issue between the two, or reveal another unexpected cause,” Petr continues. “Moreover, solving this mystery and getting a better understanding of upper solar atmospheric physics could allow us to better predict space weather in the future, potentially saving a lot of money, and even lives.”

“Watching a total solar eclipse is so amazing and unique that your breath is taken away in the first few seconds of the show. The Sun looks like it has frozen. Nature, confused by the darkness, goes to sleep, and the excitement of people is incredible. After you’ve seen it once, you can’t wait to see it again!”

Numbers in this article

| 400 | Ratio of the distance to the Sun compared to the distance to the Moon |

| 400 | Ratio of the diameter of the Sun compared to the diameter to the Moon |

| 5500 | Temperature in degrees Celsius of surface of Sun |

| 10 000 000 | Ratio of the brightness of the solar photosphere compared to the brightness of the corona |

| 2137 BCE | Year of the first written record of a total solar eclipse |

| 585 BCE | Possible year of the eclipse of Thales |

| 840 CE | Year that Louis the Pious witnessed a solar eclipse |

| 1851 CE | Year that the first accurate and scientifically useful photo of a total solar eclipse was taken |

| 1868 CE | Year that Helium was discovered during a total solar eclipse |

| 1919 CE | Year of the total solar eclipse that proved Einstein’s theory of general relativity |

Links

Biography Nicole Shearer

Among other roles, Nicole Shearer works as a Public Information Officer assistant at the European Southern Observatory. She studied Physics and Astronomy at Durham University, specialising in the public communication of astronomy. For ESO she develops various public engagement products, and helped with the preparation and testing of the education programme for the ESO Supernova Planetarium & Visitor Centre. Previously she worked in the Education department of the European Space Agency.