Comunicato Stampa

Luce fatta sul perché il 90% delle osservazioni astronomiche delle galassie distanti mancano il loro bersaglio.

24 Marzo 2010

Gli astronomi sanno da sempre che in molte osservazioni dell’Universo più distante una parte consistente della luce emessa dai corpi celesti non viene osservata. Ora, grazie ad un’indagine estremamente approfondita compiuta usando due dei quattro telescopi giganti da 8,2metri che compongono il Very Large Telescope (VLT) dell’ESO ed un apposito e specifico filtro, gli astronomi hanno determinato che una larga frazione delle galassie la cui luce impiega 10 miliardi di anni a raggiungerci è rimasta a noi sconosciuta. L’indagine ha permesso inoltre di scoprire alcune delle galassie più deboli mai trovate a questo stato iniziale dell’universo.

Gli astronomi usano frequentemente la forte , caratteristica “impronta digitale” della luce emessa dall’idrogeno conosciuta come la riga Lyman –alfa, per determinare il numero di stelle che si sono formate in un Universo molto distante [1]. C’è stato a lungo il sospetto che galassie molto distanti andassero perse in queste indagini. La nuova osservazione del VLT dimostra, per la prima volta, che questo è esattamente quello che sta accadendo. La maggior parte della luce Lyman-alfa resta intrappolata dentro la galassia che la emette, e il 90% delle galassie non si mostra alle indagini condotte in Lyman-alfa.

“Gli astronomi hanno sempre saputo che stavano perdendo qualche frazione delle galassie nelle osservazioni Lyman-alfa” spiega Matthew Hayes, il primo autore delle studio, che esce questa settimana su Nature, “ma per la prima volta ora noi abbiamo una misurazione. Il numero di galassie perse è sostanziale”.

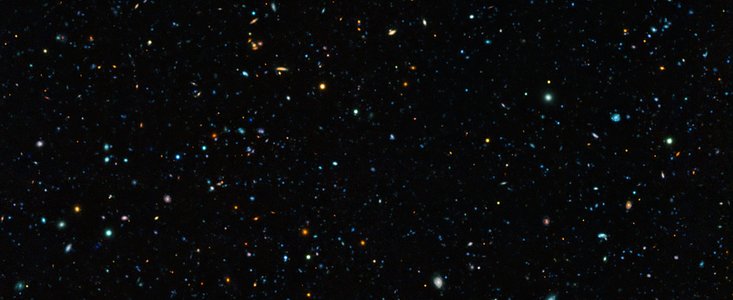

Per riuscire a capire quanto della luminosità totale andasse persa, Hayes e il suo team ha usato la camera FORS al VLT e un apposito filtro in banda stretta [2] per misurare questa luce Lyman-alfa, seguendo la metodologia standard delle osservazioni in Lyman-alfa. Poi, usando la nuova camera HAWK-I, unita ad un altro telescopio del VLT, hanno esaminato la stessa area dello spazio per luce emessa ma a una differente lunghezza d’onda, anche questa emessa dall’idrogeno eccitato, e conosciuta come la riga H-alfa. Hanno specificatamente indirizzato lo sguardo alle galassie la cui luce stava viaggiando da 10 miliardi di anni (redshift 2.2 [3]), in una ben conosciuta area del cielo, chiamata campo GOODS-South.

“E’ stata la prima volta che abbiamo osservato un pezzo di cielo così approfonditamente nella luce prodotta dall’idrogeno a queste due estremamente specifiche lunghezze d’onda, e questa prova è stata cruciale, “ dice il membro del team G?ran ?stlin. L’indagine è stata molto approfondita, e ha scoperto alcune delle galassie più deboli ora conosciute a questa epoca iniziale della vita dell’Universo. Gli astronomi possono conseguentemente concludere che le tradizionali osservazioni fatte usando la metodologia Lyman-alfa permette di vedere solo una piccola parte della luce totale prodotta, poiché la maggior parte della radiazione Lyman-alfa va persa nella interazione con le nubi interstellari di gas e polvere. Questo effetto è drammaticamente più significativo per la frequenza Lyman-alfa che per quella H-alfa. Come risulta, molte galassie, per una proporzione del 90%, vanno perse in queste indagini. “Se sono visibili dieci galassie, allora potrebbe essere che ce ne siano cento,” dice Hayes.

Differenti metodi di osservazione, basati sulla luce emessa a differenti lunghezze d’onda, condurrà ad una visione dell’Universo che è ancora incompleta. I risultati di questa indagine producono un forte avvertimento per i cosmologi, come l’”impronta digitale” Lyman-alfa diventa via via sempre più affidabile nell’esaminare le primissime galassie formatesi nella storia dell’Universo. “Ora che sappiamo quanta luce stessimo perdendo, possiamo cominciare a creare una più accurata rappresentazione del cosmo, comprendendo meglio con che velocità le stelle si siano formate in tempi differenti nella vita dell’Universo,” dice il co-autore Miguel Mas-Hesse.

La svolta è stata resa possibile grazie alle caratteristiche uniche dello strumento utilizzato. HAWK-I, che vide la prima luce nel 2007, è uno strumento “entusiasmante”. “Ci sono soltanto poche altre camere con un più ampio campo di vista di HAWK-I, ma sono telescopi grandi meno della metà del VLT. Per questo soltanto VLT/HAWK-I è in grado di trovare galassie dalla debole luminosità, per quanto distanti,” aggiunge Daniel Schaerer, componente del team.

Note

[1] la luce Lyman-alfa corrisponde alla luce emessa all’idrogeno eccitato (più specificatamente, quando gli elettroni che ruotano intorno al nucleo, saltano dal primo livello eccitato a quello più basso o fondamentale). Questa luce è emessa nella banda ultravioletta, a 121.6 nm. La riga Lyman-alfa è la prima della serie denominata Lyman, così chiamata dal suo scopritore, Theodore Lyman.

Anche la serie Balmer, da Johann Balmer, corrisponde alla luce emessa dall’idrogeno eccitato. In questo caso gli elettroni decadono al primo livello eccitato. La prima riga in questa serie è la H-alfa, emessa a 656.3 nm.

Dato che la maggior parte degli atomi di idrogeno presenti in una galassia sono al livello fondamentale, la radiazione Lyman-alfa viene assorbita più efficacemente che quella H-alfa, la quale richiede atomi che abbiano un elettrone in un secondo livello. Dato che questo è molto raro nel freddo idrogeno interstellare che permea le galassie, il gas è quasi perfettamente trasparente alla frequenza H-alfa.

[2] Un filtro a banda stretta è un filtro ideato per far passare soltanto uno stretto intervallo di frequenze della radiazione, centrato intorno a una specifica lunghezza d’onda. I filtri a banda stretta tradizionali includono le righe della serie Balmer e H-alfa.

[3] Poiché l’Universo si espande, la luce di un oggetto distante si sposta verso il rosso (redshift) in una misura che dipende dalla distanza stessa. Questo vuol dire che la lunghezza d’onda della luce aumenta. Un redshift 2.2 - corrisponde a galassie la cui luce ha impiegato dieci miliardi di anni a raggiungerci – che vuol dire che la lunghezza d’onda della luce è aumentata di un fattore 3.2. Così la luce Lyman-alfa è ora vista a circa 390 nm, nei pressi della radiazione visibile, e può essere osservata con lo strumento FORS installato al VLT dell’ESO, mentre la riga H-alfa è spostata alla lunghezza d’onda di 2.1 micron, nella banda del vicino infrarosso. Così da poter essere osservata con lo strumento HAWK-I su VLT.

Ulteriori Informazioni

Questa ricerca è stata presentata in una pubblicazione che appare su Nature (“Escape of about five per cent of Lyman-a photons from high-redshift star-forming galaxies”, by M. Hayes et al.).

Il team è composto da Matthew Hayes, Daniel Schaerer, e Stéphane de Barros (Observatoire Astronomique de l'Université de Genève, Switzerland), Göran Östlin e Jens Melinder (Stockholm University, Sweden), J. Miguel Mas-Hesse (CSIC-INTA, Madrid, Spain), Claus Leitherer (Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, USA), Hakim Atek and Daniel Kunth (Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris, France), e Anne Verhamme (Oxford Astrophysics, U.K.).

L’ESO (European Southern Observatory) è la principale organizzazione intergovernativa di Astronomia in Europa e l’osservatorio astronomico più produttivo al mondo. È sostenuto da 14 paesi: Austria, Belgio, Repubblica Ceca, Danimarca, Finlandia, Francia, Germania, Italia, Olanda, Portogallo, Spagna, Svezia, Svizzera e Gran Bretagna. L’ESO mette in atto un ambizioso programma che si concentra sulla progettazione, costruzione e gestione di potenti strutture astronomiche da terra che consentano agli astronomi di fare importanti scoperte scientifiche. L’ESO ha anche un ruolo preminente nel promuovere e organizzare cooperazione nella ricerca astronomica. L’ ESO gestisce tre siti unici di livello mondiale in Cile: La Silla, Paranal e Chajnantor. A Paranal, l’ESO gestisce il Very Large Telescope, l’osservatorio astronomico nella banda visibile più d’avanguardia al mondo. L’ESO è il partner europeo di un telescopio astronomico rivoluzionario, ALMA, il più grande progetto astronomico esistente. L’ESO sta pianificando al momento lo European Extremely Large Telescope che opererà nell’ottico e nel vicino-infrarosso di 42 metri, l’E-ELT, che diventerà “il più grande occhio del mondo rivolto al cielo”.

Links

Contatti

Matt Hayes

Observatory of Geneva, Switzerland

Tel.: +41 22 379 24 32

Cell.: +41 76 243 13 55

E-mail: matthew.hayes@unige.ch

Miguel Mas-Hesse

Centro de Astrobiologia (CSIC-INTA), Spain

Tel.: +34 91 813 1196/1161

Cell.: +34 615145651

E-mail: mm@cab.inta-csic.es

Göran Östlin

Department of Astronomy

Stockholm University, Sweden

Tel.: +46 8 55 37 85 13

E-mail: ostlin@astro.su.se

Henri Boffin

VLT Press Officer

ESO, Garching, Germany

Tel.: +49 89 3200 6222

Cell.: +49 174 515 43 24

E-mail: hboffin@eso.org

Joerg Gasser (press contact Svizzera)

Rete di divulgazione scientifica dell'ESO

E-mail: eson-switzerland@eso.org

Sul Comunicato Stampa

| Comunicato Stampa N": | eso1013it-ch |

| Nome: | GOODS South field |

| Tipo: | Early Universe : Galaxy : Grouping : Cluster |

| Facility: | Very Large Telescope |

| Instruments: | FORS1, HAWK-I |

| Science data: | 2010Natur.464..562H |

Our use of Cookies

We use cookies that are essential for accessing our websites and using our services. We also use cookies to analyse, measure and improve our websites’ performance, to enable content sharing via social media and to display media content hosted on third-party platforms.

ESO Cookies Policy

The European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) is the pre-eminent intergovernmental science and technology organisation in astronomy. It carries out an ambitious programme focused on the design, construction and operation of powerful ground-based observing facilities for astronomy.

This Cookies Policy is intended to provide clarity by outlining the cookies used on the ESO public websites, their functions, the options you have for controlling them, and the ways you can contact us for additional details.

What are cookies?

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on your device by websites you visit. They serve various purposes, such as remembering login credentials and preferences and enhance your browsing experience.

Categories of cookies we use

Essential cookies (always active): These cookies are strictly necessary for the proper functioning of our website. Without these cookies, the website cannot operate correctly, and certain services, such as logging in or accessing secure areas, may not be available; because they are essential for the website’s operation, they cannot be disabled.

Functional Cookies: These cookies enhance your browsing experience by enabling additional features and personalization, such as remembering your preferences and settings. While not strictly necessary for the website to function, they improve usability and convenience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent.

Analytics cookies: These cookies collect information about how visitors interact with our website, such as which pages are visited most often and how users navigate the site. This data helps us improve website performance, optimize content, and enhance the user experience; these cookies are only placed if you provide your consent. We use the following analytics cookies.

Matomo Cookies:

This website uses Matomo (formerly Piwik), an open source software which enables the statistical analysis of website visits. Matomo uses cookies (text files) which are saved on your computer and which allow us to analyze how you use our website. The website user information generated by the cookies will only be saved on the servers of our IT Department. We use this information to analyze www.eso.org visits and to prepare reports on website activities. These data will not be disclosed to third parties.

On behalf of ESO, Matomo will use this information for the purpose of evaluating your use of the website, compiling reports on website activity and providing other services relating to website activity and internet usage.

Matomo cookies settings:

Additional Third-party cookies on ESO websites: some of our pages display content from external providers, e.g. YouTube.

Such third-party services are outside of ESO control and may, at any time, change their terms of service, use of cookies, etc.

YouTube: Some videos on the ESO website are embedded from ESO’s official YouTube channel. We have enabled YouTube’s privacy-enhanced mode, meaning that no cookies are set unless the user actively clicks on the video to play it. Additionally, in this mode, YouTube does not store any personally identifiable cookie data for embedded video playbacks. For more details, please refer to YouTube’s embedding videos information page.

Cookies can also be classified based on the following elements.

Regarding the domain, there are:

- First-party cookies, set by the website you are currently visiting. They are stored by the same domain that you are browsing and are used to enhance your experience on that site;

- Third-party cookies, set by a domain other than the one you are currently visiting.

As for their duration, cookies can be:

- Browser-session cookies, which are deleted when the user closes the browser;

- Stored cookies, which stay on the user's device for a predetermined period of time.

How to manage cookies

Cookie settings: You can modify your cookie choices for the ESO webpages at any time by clicking on the link Cookie settings at the bottom of any page.

In your browser: If you wish to delete cookies or instruct your browser to delete or block cookies by default, please visit the help pages of your browser:

Please be aware that if you delete or decline cookies, certain functionalities of our website may be not be available and your browsing experience may be affected.

You can set most browsers to prevent any cookies being placed on your device, but you may then have to manually adjust some preferences every time you visit a site/page. And some services and functionalities may not work properly at all (e.g. profile logging-in, shop check out).

Updates to the ESO Cookies Policy

The ESO Cookies Policy may be subject to future updates, which will be made available on this page.

Additional information

For any queries related to cookies, please contact: pdprATesoDOTorg.

As ESO public webpages are managed by our Department of Communication, your questions will be dealt with the support of the said Department.