- What the giant belt of debris lying beyond Neptune is

- How astronomers study similar belts around other stars

- What these belts tell us about the origins and evolution of planetary systems

Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and… Those of you that continued the sentence with ‘Pluto’ already know it: there are other objects lurking beyond the orbit of Neptune. Hundreds of thousands of objects are encircling our Solar System in the so-called Kuiper Belt. Now, a one-of-a-kind survey has revealed a total of 74 other similar belts surrounding planetary systems close to our own. Of all shapes, ages and sizes, astronomers are finding that examining this collection of belts can teach us a lot about the origin and evolution of planetary systems, including our own.

From dust to belt

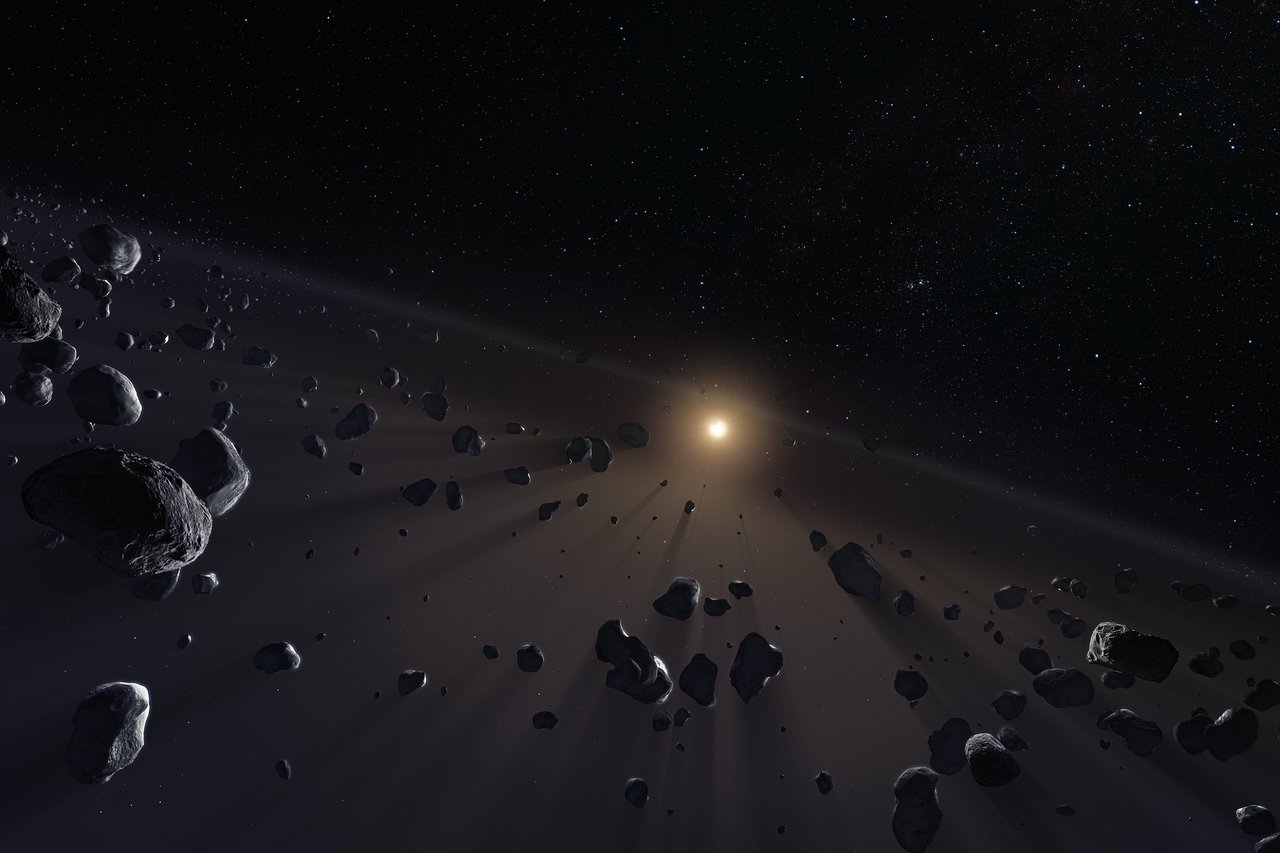

The Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt (or simply, Kuiper Belt) [1] is a huge structure extending between 30 to 50 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun, full of icy and rocky objects. But where does it come from?

In its infancy, the Sun was surrounded by a giant rotating cloud of gas and dust. Much like making a pizza from a ball of dough, by rotating over time, the cloud eventually became a flat disc, which we call a protoplanetary disc.

There, grains of dust collided and fused into increasingly large structures, and once they reached a kilometre-size, their own gravity started to attract more objects, fuelling their growth even further. This is — in a very summarised version — how we think planets formed. We have actually seen this process taking place in other planetary systems beyond our own. However, we also know that not all dust ended up forming planets.

Astronomers think that the influence of large planets like Neptune could have prevented dust beyond its orbit from creating new planets, leaving us with just a belt of debris. This debris, though, is actually a hidden space treasure.

Today, the Kuiper Belt is a collection of dusty and icy space rocks, ranging from dust grains and pebbles to comets and dwarf planets. From a few millimetres to kilometres in diameter, many of these objects have changed little since their formation. Frozen (literally) in time, these are remnants of the early stages of the Solar System, and tell us a lot about its initial properties.

Belts of debris like the Kuiper Belt exist in other planetary systems too. They are broadly known as “planetesimal belts”, since the objects within them have the potential to coalesce to form planets, or “exocomet belts”, since they are usually hiding comets (icy planetesimals) within them. But how can we observe these belts?

A journey in search of other belts

At first glance, finding exocomet belts should be easy given how large they are. However, belts have actually been difficult to observe and image.

The reason behind this is their temperature. The objects lying within an exocomet belt are very far from their host star, and thus, they are extremely cold. In the Kuiper belt, for example, temperatures range from -250 to -150 degrees Celsius. At these low temperatures, belts only shine at long wavelengths, making them difficult to observe for most — but not all — telescopes.

One of the telescopes that can observe them is the Atacama Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). Operated by the European Southern Observatory and its partners, this array of 66 antennas in northern Chile is specifically designed to detect long wavelength radiation from cold astronomical sources, like exocomet belts.

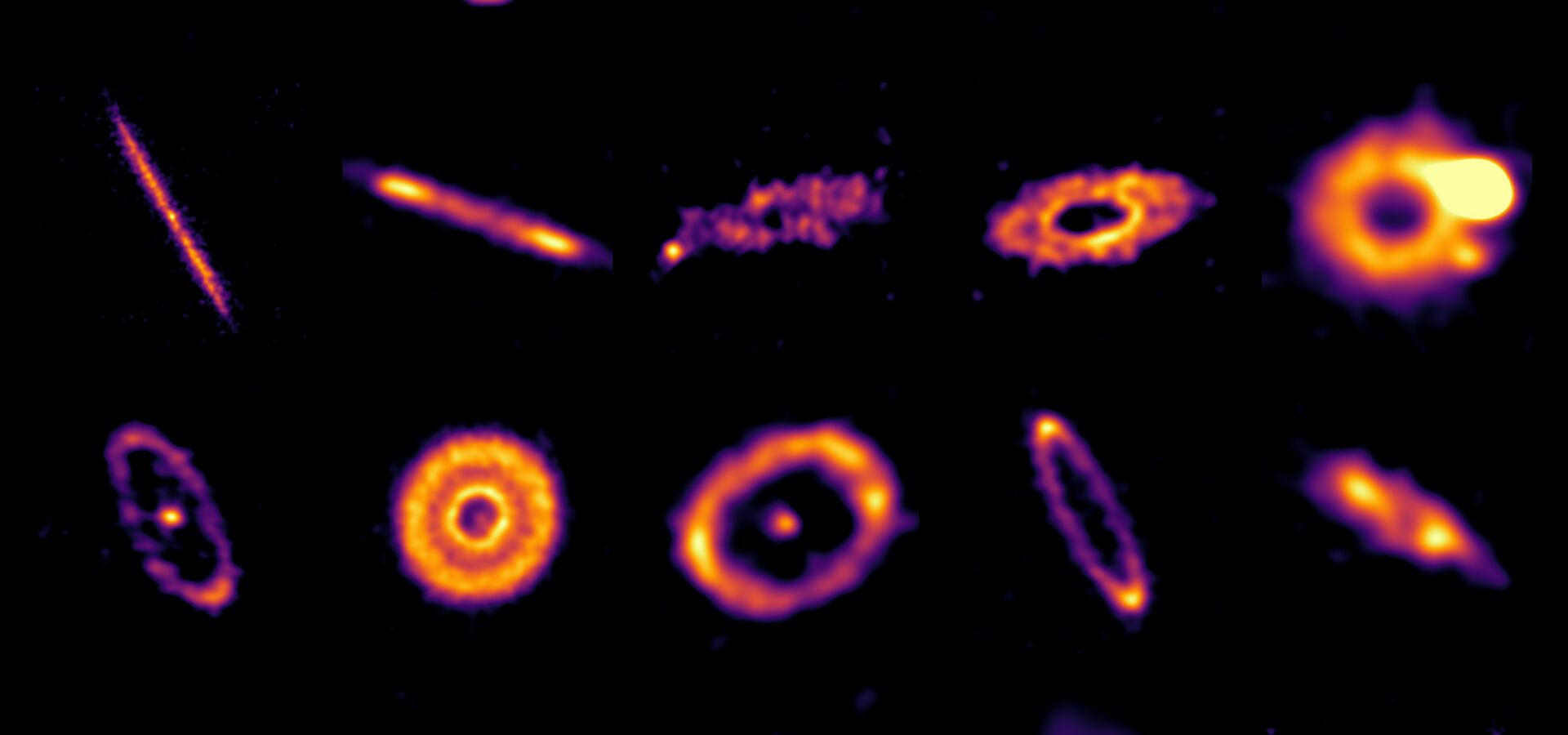

Using ALMA, the Hawaiian Submillimeter Array (SMA) and archival data, a team led by Luca Matrà, an associate professor at the University of Dublin, has embarked on a mission to image as many exocomet belts as possible, in all stages, from newly formed to very mature. The survey, named REASONS [2] is the largest of its kind, to date.

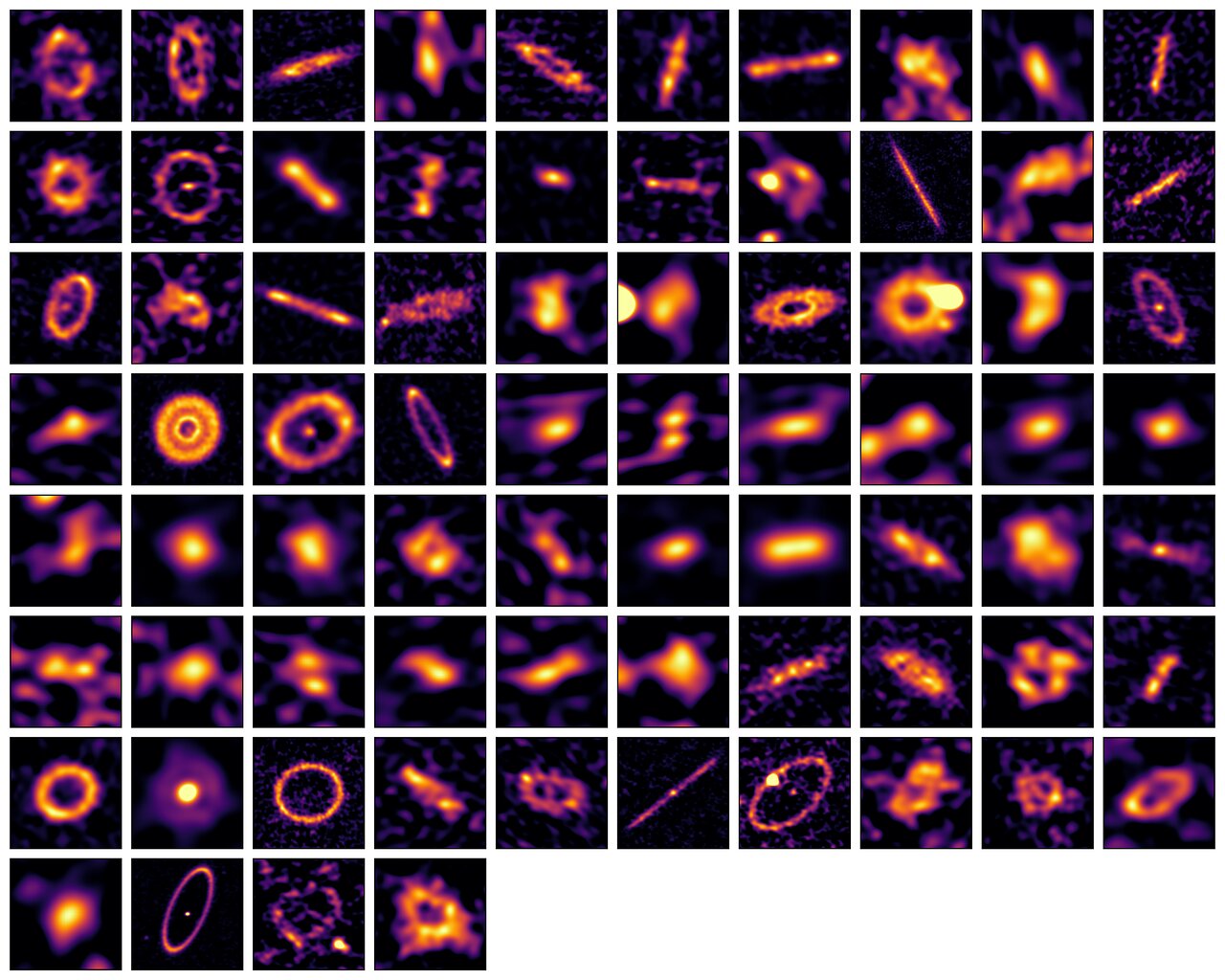

The survey contains images of 74 belts around “nearby” planetary systems found within 500 light-years from us. These results have now been published in Astronomy and Astrophysics, and they are already challenging the ideas astronomers had about these structures.

Where did all the small, thin belts go?

Not all belts are equal. The REASONS survey has revealed that exocomet belts come in all shapes, sizes and ages, but within this variation, scientists are starting to see some patterns.

One of these patterns is that belts are remarkably larger than expected. Smaller belts are closer to their host star, making them hotter, brighter and theoretically easier to find. And yet, the new observations indicate that they are very rare. This means that either most belts form further out, or that smaller belts are less massive, and, in fact, harder to detect.

The team also confirmed previous findings: as belts evolve, collisions within them smash their large objects into smaller ones. If this process were to happen faster in belts closer to their stars, it could also explain why the team didn’t find small belts.

Belts are not only larger than previously thought, but also extend more widely. Think of a doughnut with a small hole, rather than an onion ring. Narrower belts — what we would call “rings” — are uncommon in the survey.

One possibility is that belts broaden out as time goes by. The first results from this survey, though, found that older belts are not necessarily broader, indicating that this is probably not the case. Another possibility is that wide belts have gaps within them that would split them into narrower rings, but that we can’t see, yet.

Belts and the Earth: enemies or allies?

This is not the end of the story of belts, though. Researchers think that future telescopes will be able to uncover substructures within belts, like gaps and rings. Belts could even be hiding dwarf planets much like Pluto, ready to be discovered.

But studying these belts is more than space treasure hunting, it is also learning about the history of our Solar System and our own planet.

Earth is always keeping an eye on the Kuiper Belt, a big source of asteroids and comets [3]. Since an asteroid caused a major extinction 65 million years ago, it is understandable why we would be concerned. However, one theory suggests that at least some of Earth’s water may have also arrived from the Kuiper Belt, known to be a giant repository of frozen water. Large far-away planets like Neptune or Uranus may have had a crucial role in propelling water-carrying comets toward us, providing an element that would otherwise be quite rare on the primitive Earth. Only time will tell whether we owe our lives to space rocks.

As we get to know more about exocomet belts, we may finally be able to understand the role that belts play in the formation and evolution of planetary systems.

Notes

[1] The most common way to refer to this structure is Kuiper Belt, after Dutch astronomer Gerard Kuiper, who hypothesised its existence based on models for the formation of the Solar System. Another astronomer, the Irish Kenneth Edgeworth, had already speculated about this structure before, but the idea predates both astronomers. Larger objects in the belt are often called “trans-Neptunian objects”, too.

[2] REASONS is an acronym that stands for REsolved ALMA and SMA Observations of Nearby Stars.

[3] Many of the asteroids and comets we see may have come from this distant region. Some, like this year’s Tsuchinshan-ATLAS comet, come from a structure even farther away, called the Oort Cloud, while others, like the mysterious interstellar object Oumuamua, originated from somewhere beyond our Solar System.

Biography Alejandro Izquierdo López

Alejandro is an evolutionary biologist from Spain who has been researching the ancestors of shrimps, centipedes and insects, trying to understand how evolution worked 500 million years ago. He has discovered several strange-looking extinct animals such as the “Pac-man crab” Pakucaris or the “Cambrian-beagle” Balhuticaris. He also loves communicating any type of science, including (of course), astronomy. At ESO, he aims to strengthen his communication skills while re-igniting his childhood passion for the cosmos.