- What ALMA is and how it observes the coldest regions of the universe

- How three international partners made this ambitious project possible

- Some personal memories of ALMA’s early days from those who lived them

At 5000 metres above sea level, high in the Chilean Andes, the Chajnantor plateau is one of the loneliest places on Earth. It is, however, home to ALMA, a giant array of 66 antennas spread over 16km, turning their great white heads in graceful unison to look deep into the distant Universe.

“What we can see with ALMA is the cold Universe, regions dark to our eyes but that shine bright at millimetre/submillimetre wavelengths,” explains de Gregorio-Monsalvo. “With ALMA we can mainly see cold dust and gas coming from different regions of the Universe, from very distant galaxies to nearby objects, revealing with unprecedented detail how galaxies, stars and planets form and evolve, and the building blocks of life.”

As a project, ALMA is unprecedented both in scale and in its pioneering example of international collaboration in astronomy. Despite the isolation of its surroundings, it was the coming together of different cultures and organisations that made its conception possible. But it wasn’t always going to be that way...

“The ALMA project was a dream that various astronomers across the world began to form back in the 1990s”, explains Hills. “A lot of people working in the field [of millimetre-wavelength astronomy] realised that they needed a much bigger telescope and, in particular, a telescope that used lots of relatively large antennas spread over a really large region.”

Such a telescope is called an interferometer, which works by combining the light from each of its antennas to discern much finer details than would be possible with an individual antenna. The technique is notoriously challenging — “Interferometry is a very tricky beast!” confirms Andreani.

Initially, three separate groups in Europe, Japan and the USA developed plans for such a telescope. But it soon became apparent that the best way to realise this dream would be to merge these projects, creating one large facility instead of three separate ones. The three major astronomical institutes that agreed to undertake this ambitious project were ESO in Europe, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in the USA, and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) in East Asia. The three partners also shared the construction of the antennas, with slightly different designs but ultimately the same specifications. ESO and NRAO would provide 25 12-m antennas each, and NAOJ would contribute 4 12-m antennas and 12 7-m ones.

Once the partners had come together and the plans for the three projects were developed into a single telescope design, ALMA started to come to life in 2001, with plans for a 10-year construction period. Working as a Project Scientist, Hills was able to experience first hand some of the challenges and triumphs of this process. “I think the original plan back in 2000 was that we would be ready for this so-called early science period, in 2007, and by 2007 we hadn’t even got the first antenna!” he says.

Fortunately after a slow start, ALMA’s construction quickly picked up pace. “There was no time to be bored!” says de Gregorio-Monsalvo. “There were so many things to develop and test to make ALMA possible that the first light seemed really far-off. But thanks to the effort of a great team the goal was achieved.”

|

|

In September 2011, ALMA opened for its “early science” period, with astronomers from across the globe able to use the new telescope for the first time. At this time only 16 of the eventual 66 antennas were available to use. Even then, ALMA was still bigger in scale than any previous interferometer and the excitement among the astronomical community was palpable. To observe with ALMA –– or any other telescope –– astronomers must submit proposals that are evaluated by a panel of experts; only a few will be successful. For this first observation period, ALMA received over 900 proposals, but only around 100 were selected!

“The thing that was amazing was that as soon as all the equipment came together, everything worked more or less out of the box,” remembers Hills. “The first images came out and the scientific results started to flow. The results were fantastic –– well beyond our expectations in many cases.”

“It was amazing in terms of human relation and amazing in terms of scientific discovery.” agrees Adreani.

De Gregorio-Monsalvo also remembers how she felt at ALMA first light: “It was very rewarding for me and I felt very proud of myself and of my ALMA colleagues. When I saw the first light I thought that all the invested effort and all the sleepless nights had been worth it.”

|

De Gregorio-Monsalvo and Andreani in front of an ALMA antenna on top of one of the transporters.

Credit: I. de Gregorio-Monsalvo, P. Andreani

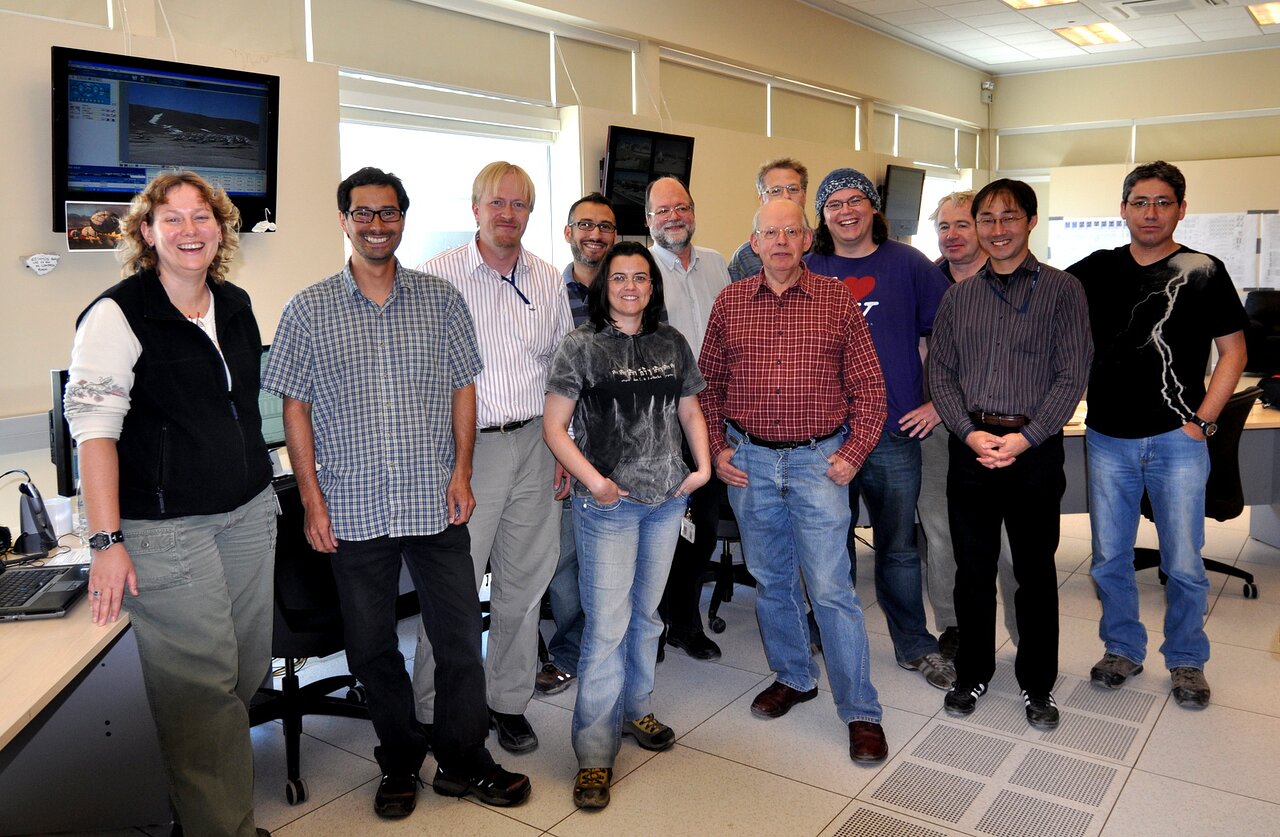

Part of the ALMA team during the execution of the first scheduled observations, including de Gregorio-Monsalvo and Hills at the centre.

Credit: R. Hills.

|

During the construction of ALMA in Chile, other challenges were being tackled behind the scenes as the ALMA partners worked to define how the observatory would be operated. Three ALMA Regional Centres (ARCs) were created to interact with astronomers worldwide. “It was the first time that a big international facility built this kind of user support mode which was spread around,” says Andreani. “The main difficulty really was to communicate, and to convince people that we are always working towards the same goal — we all wanted to make this facility work and be successful. We built the entire operation. The first years were pretty intensive. We set up all the procedures, we agreed on all the policies, we wrote all the documents which are now available both for public and for internal purposes,” she says.

Ultimately the leap into the unknown regarding the organisation of ALMA paid off and Adreani felt the ARCs were especially successful. “I see that still the people supporting the users are doing a wonderful job, they are offering more and more help. I think it's now a model which many other facilities are copying.”

Now, a decade after it opened for early science, ALMA has been at the forefront of many discoveries. “My favourite scientific discovery made by ALMA was the image of the dust disc surrounding the young star HL Tau, revealing the planetary genesis,” says de Gregorio-Monsalvo. “I still remember the awed silence of the team after we saw that image for the first time!” Hills agrees: “When that first came out it just blew our minds.”

|

|

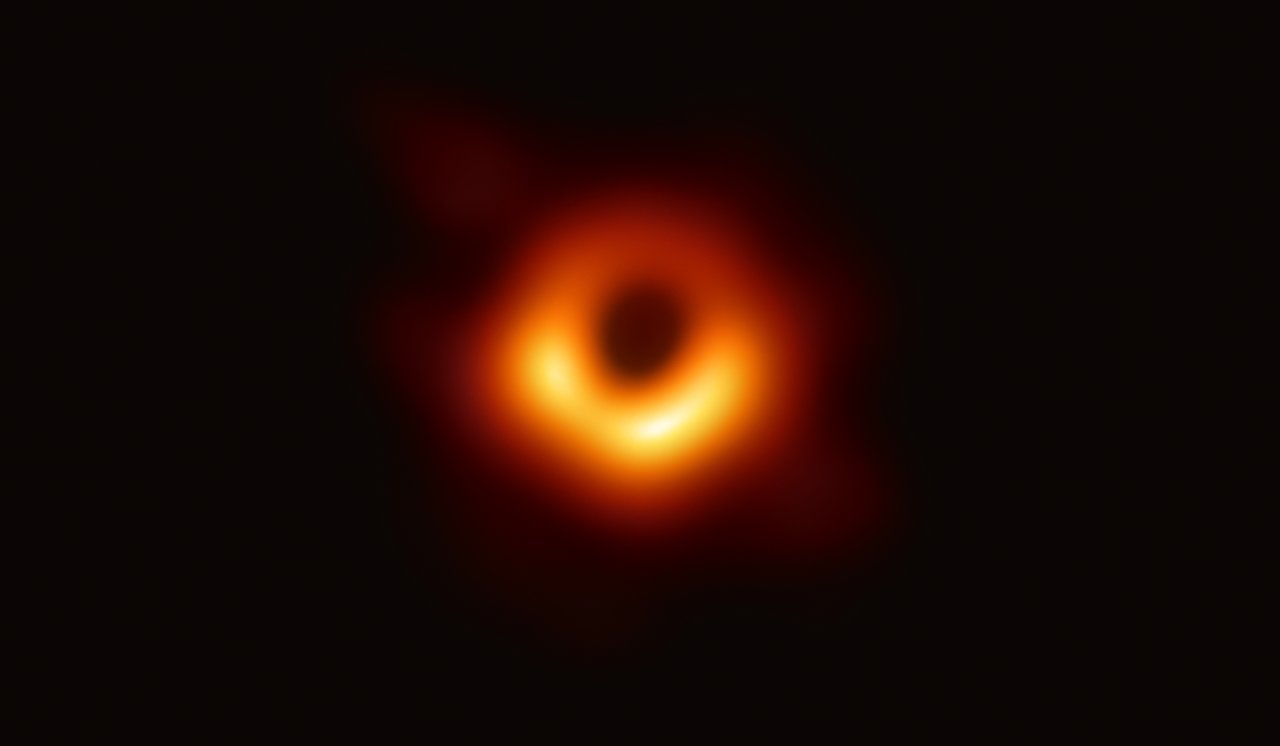

Another scientific highlight with ALMA is the role it played in the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration to deliver the first image of a black hole, the supermassive black hole at the heart of the M87 galaxy. This was an impressive feat, as it required combining data gathered by several radio telescopes all over the world, functioning as a single planet-sized facility. “When we built the telescope we knew the science specifications that needed to be reached, but we were not prepared to see transformational science in just one single image,” says de Gregorio-Monsalvo.

“Indeed it is delivering very astonishing results in all astronomical fields,” adds Andreani.

In addition to its scientific achievements, all the scientists agree that ALMA has been a triumph of cooperation on a global scale. “It holds up as an example of international collaboration paying off. It certainly couldn’t have been done in its successful form by a single one of the partners,” says Hills.

Links

- ALMA opens it eyes

- ALMA Observatory webpage

- Virtual tour of ALMA, also in virtual reality format

- ALMA images and videos in the ESO archive

Biography Thea Elvin

Thea Elvin is Press Officer at The Lancet. Before she was a science journalism intern at ESO. She has completed an undergraduate degree in Natural Sciences at the University of Cambridge (UK) and a master’s degree in Climate and Atmospheric Science at the University of Leeds (UK) and is currently pursuing a career in science communications.