How Productive is the Very Large Telescope?

Nando Patat on evaluating ESO’s science output

- How astronomers apply to use the world’s most advanced visible-light observatory

- How ESO measures its scientific performance

- How much VLT time results in published science papers

- Why some telescope time goes unused

Q: Tell us a little about yourself and your research at ESO.

A: Since I first looked at the Moon with my father’s binoculars, I have been passionate about astronomy. Although I was torn between science and music, I finally made the decision to study astronomy. I obtained a Masters from the University of Padova, Italy, the same place where Galileo first pointed his cannocchiale (an early telescope) to the heavens. I then moved to ESO Headquarters in Germany to start PhD work, before moving to La Silla as an ESO Fellow. During those intense years, my passion for the night sky became scientifically mature; a fortunate series of events led me to become serious about professional astronomy.

Since then, my career has developed at ESO. Being a restless person, I have changed jobs quite a bit in my twenty years here, most recently to the Observing Programmes Office, which I have led since 2011. The department is in charge of managing time allocation for all ESO telescopes, which sounds easier than it is! When I am not busy, I explore my original scientific passion for supernovae.

Q: Can you talk us through how astronomers apply for observing time on ESO telescopes?

A: The art of writing a proposal boils down to explaining how the proposer will answer an important astronomical question. In short, it means writing a fascinating “story”! Every semester about 900 proposals are submitted to ESO, involving more than 3500 scientists from about fifty countries. This is roughly a third of the active astronomers on the planet, so the competition is fierce. This is why the “story” needs to be better than good: it needs to be excellent.

Once the applicant has prepared their “story”, they submit it to the Observing Programmes Committee (OPC). This is an important body of about 80 experts, who are asked to rank the applications on behalf of the astronomical community. As the OPC members are nominated by astronomers, this is a democratic process for telescope users to decide what science is most worthwhile.

The referees have four weeks to review the proposals. Once the OPC has made a first assessment, the bottom 30% of the proposals are discarded. The panels then physically convene in a meeting that lasts three days, in which the surviving applications are discussed, ranked, and made into a final list, which is used to allocate telescope time. The final result is submitted to the Director General for approval and then announced. Because of the oversubscription rate of ESO telescopes, only about a quarter of the applicants get observing time.

Q: Scientists usually get excited about publishing results — what made you decide to study the opposite, namely non-publishing scientific programmes at ESO?

A: An organisation the size of ESO needs to assess its performance and identify possible areas of improvement, and there are a number of ways to do this. The core task of ESO is building and operating world-class telescopes: a task at which we’re pretty successful! However, the ultimate purpose of all these efforts is to advance science, and assessing how much a telescope contributes to this is a complex (and sometimes controversial) task. Scientific progress is hard to quantify, and sometimes even hard to describe — it may take decades before the importance of a scientific discovery is fully appreciated. However, since scientific results are primarily communicated via peer-reviewed publications, a natural way to measure the overall success of a telescope is its publication rate. This is why we asked “How much telescope time eventually results in at least one refereed publication?”

ESO had already asked this question for its flagship observing machine, the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at the Paranal Observatory in Chile, in an earlier analysis. The results revealed a surprising fact: about half of VLT observations do not turn into a refereed publication. Put crudely (and a little unfairly), about half of the telescope time is “wasted”. As usual, things are more complex than they appear at first glance, but this definitely called for further investigation. The Survey of Non-Publishing Programmes (SNPP) was created, and set out to explain “wasted” telescope time.

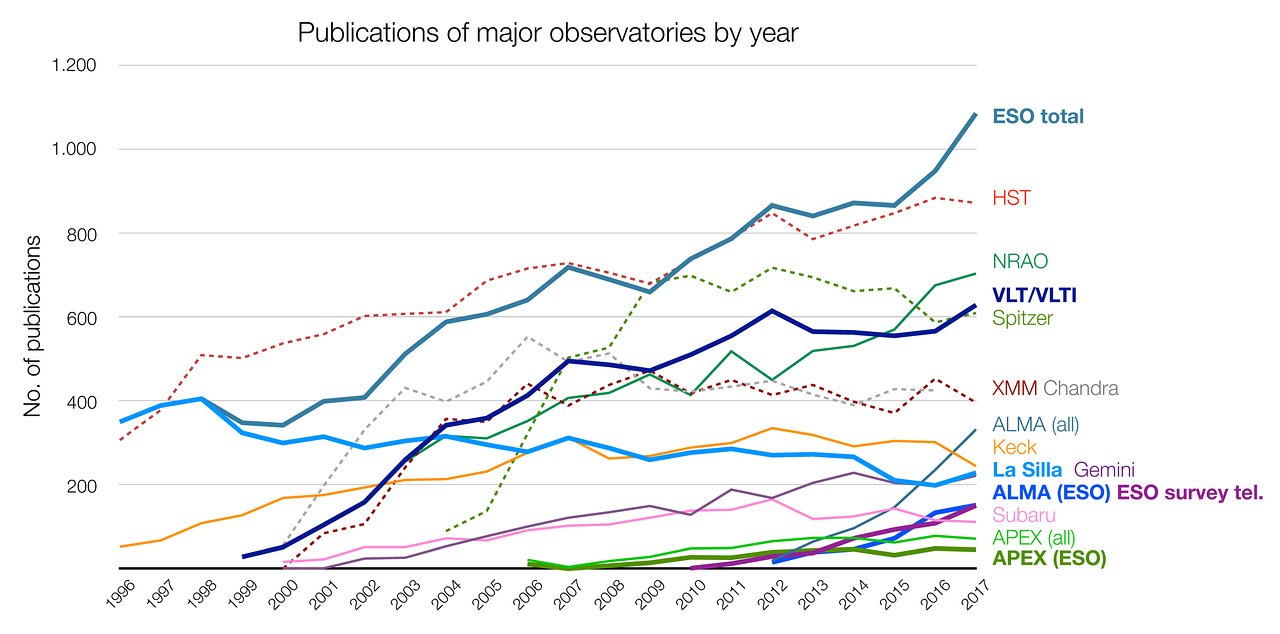

However, don’t get me wrong — ESO is doing well: since the start of VLT operations, the publication rate of ESO has been steadily growing, reaching 1000 publications per year in 2017. The question is: can we do better?

Q: Is the number of published scientific papers the only way to measure the performance of ESO telescopes?

A: Certainly not! The fraction of accepted programmes that turn into publications is only one of many ways of measuring performance. For instance, you can go one step further and estimate the scientific impact of publications based on ESO data. This is done by counting the number of times a paper is cited by other papers, which provides a rough indication of how important a published finding is.

However, this is not the full story. You could also say that the success of ESO can be measured by the number of applications we receive or by the number of distinct users, both of which reflect the interest in our telescopes within the astronomical community. You could also measure the success of our facility in terms of user satisfaction, and many other ways. A completely comprehensive performance indicator would take all these aspects into account, but exactly how is a matter of animated debate.

Q: What was the most interesting thing you discovered about the performance of ESO telescopes? Did anything surprise you?

A: One of the main results of the SNPP is that there is not a single reason that explains the observed publication return. One interesting fact was that the favourite answer for not publishing was: “I am still working on the data.” This may at first seem like just a bad excuse — a professional version of the popular line “the dog ate my homework” — but it really does take a long time to publish data. One of the surprises was that the time taken to get from an approved proposal to a scientific publication is three and a half years for half of these projects, and more than 10 years to reach 75% — astronomers really are still working years after they receive data. The bottom line is that, after correcting for the publication delay in the latest survey, the fraction of "wasted" time reduces to about 25%.

Q: Could the fraction of unpublished science from ESO telescopes just be a side effect of the trial-and-error nature of the scientific process?

A: “Inconclusive results” were indeed the culprit in about 12% of cases. Although this is not enough to explain the observed rate, it is still relevant. The problem is not that there are negative results, but rather that these negative results are not published. This is a real issue in all scientific disciplines, not just astronomy. The reasons for this worrisome trend have to do with the lack of resources and the pressure to publish appealing results. If researchers have to choose between a publication reporting a negative result and one presenting a very exciting finding, they certainly opt for the latter. This is understandable, but affects the scientific method at its very roots. Although counter-measures are being taken, the publication of negative results remains a low-priority task for scientists.

Q: One of the interesting findings from your research was that scientists using ESO telescopes don’t have the resources to sift through all the data they get back. Could it be the case that ESO telescopes are producing more information than the astronomical community can deal with?

A: About 10% of replies cited lack of resources as the reason for not publishing. Considering the long time it takes to publish, this means they may have access to more data than they can cope with. The ESO community has been steadily growing from about 1500 users at the start of VLT operations to about 3500 today. However, this growth was apparently not enough to keep up with the amount of data available. This may be related to funding problems, and the difficulty of attracting and keeping young astronomers, but that’s a different discussion...

Q: You found that programmes that observe for longer are more likely to get published — do you think ESO should only focus on big observing programmes?

A: An average VLT Normal programme lasts around 15 hours, with a very few lasting more than 25 hours. There are also Large Programmes that request more than 100 hours. About 15% of the total VLT time is spent on Large Programmes, and if we were to allocate more telescope time to larger projects, we’d have less time for smaller ones. Although these smaller projects are individually less productive, they are much more numerous and therefore significantly contribute to the overall productivity.

In broader terms, suppose that an observatory gets 1000 citations/year from papers based on data gathered with its telescopes. This can be produced by 1000 papers with one citation each, or by one single paper with 1000 citations alone, and all possible combinations in between. The “success” is the same, but in terms of absolute impact (i.e., findings that “go down to history”), the second extreme case is incomparably better than the first.

For an intergovernmental organisation like ESO, this is a difficult problem, but the solution is most likely one in which ESO maintains a healthy diversity in the scale of projects. Though large projects may lead to big breakthroughs, just a few hours of telescope time can lead to major findings, opening new avenues for larger projects to follow up. There is certainly an ideal distribution of programme lengths that would maximise the number of papers produced, and we’re trying to find it!

Q: Finally, do you think ESO can become more successful at turning observing time into published papers?

A: At the moment it seems that there is some room for improvement. There are things ESO can’t address, but we can certainly improve certain aspects. These range from a better proposal selection and time allocation (admittedly not an easy task!) to enhanced operational procedures. The astronomical community can also optimise the distribution of resources to ensure that data can be analysed effectively as soon as it becomes available. However, in the purest spirit of the scientific method we have to attempt some risky projects — if we want to keep expanding our knowledge of the Universe, we will never reach a 100% return. Luckily, we know that the archived data will also serve generations of astronomers in the future.

Numbers in this article

|

25% |

The percentage of successful proposals for VLT time |

|

900 |

The number of proposals for telescope time ESO receives every semester |

|

3500 |

The number of astronomers applying for time on ESO telescopes |

|

75% |

The amount of projects using the VLT that result in published science within 10 years after observing |

Links

- Science Paper: The ESO Survey of Non-Publishing Programmes

Biography Nando Patat

Ferdinando (Nando) Patat holds a Masters and a PhD in Astronomy from the University of Padova, Italy. He was an ESO student in Garching and a postdoctoral ESO Fellow at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. He currently leads ESO’s Observing Programmes Office, the department in charge of telescope time allocation. A member of numerous international collaborations, he mainly works in the field of supernova explosions in the local Universe.