- Why the Leo Ring was such an unexpected discovery

- The long-sought origins of the Leo Ring

- How old theories are challenged by new evidence

In 1983, a team of astronomers led by PhD student Stephen E. Schneider was aiming to measure the properties of a distant galaxy and needed a “blank sky” reference measurement. Pointing the US Arecibo radio telescope at what they thought was an unremarkable patch of the sky, they found it was actually populated with cold hydrogen gas, revealing a giant gas cloud six times larger in diameter than the Milky Way. It was named the Leo Ring after its shape and for lying in the direction of the Leo constellation in the sky.

The discovery of such a large gas cloud, and the lack of any stars detected in the ring, raised questions on how galaxies form and evolve. A gas cloud of this size should have collapsed under gravity to become one or more galaxies containing many stars.

If the gas forming this structure had never been part of a galaxy, could the Leo Ring be an ancient cloud of gas left over from billions of years ago when galaxies were still forming? Or perhaps the gas was part of a galaxy, but it was stripped away from it and expanded to form the Leo Ring? However, even in the latter case, we would still expect to see some stars, either left over from a galaxy or created in the violent process of gas expansion.

Now, nearly 40 years after its discovery, a new team of astronomers led by Edvige Corbelli from Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory, National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) in Italy have tackled these questions conclusively.

Stars are the key to determining the history of the Leo Ring. “The only way to solve the mystery of the Leo Ring’s origins is to measure the amount of heavy elements dispersed in the hydrogen gas,” explains Corbelli. “These elements are created by stars and, if found in large amounts, they could give a clear signal that the gas is not primordial.”

The Leo Ring was widely believed to be a primordial cloud of gas, containing only the lightest elements — hydrogen, helium and a trace amount of lithium — that were created in the Big Bang, with no stars. Then in 2009, a team led by David Thilker of the John Hopkins University were studying the first ultraviolet (UV) observation of Messier 96, when they made a serendipitous discovery. On noticing that the Leo Ring was visible at the edge of their image, they were able to identify clumps shining brightly in the UV that were possibly associated with the ring and could signal the presence of massive stars. This challenged the then-held theory that the ring lacked stars. However, astronomers could still not say for certain whether stars were forming in the Leo Ring, or whether they were picking up signatures of stars much further away in the background.

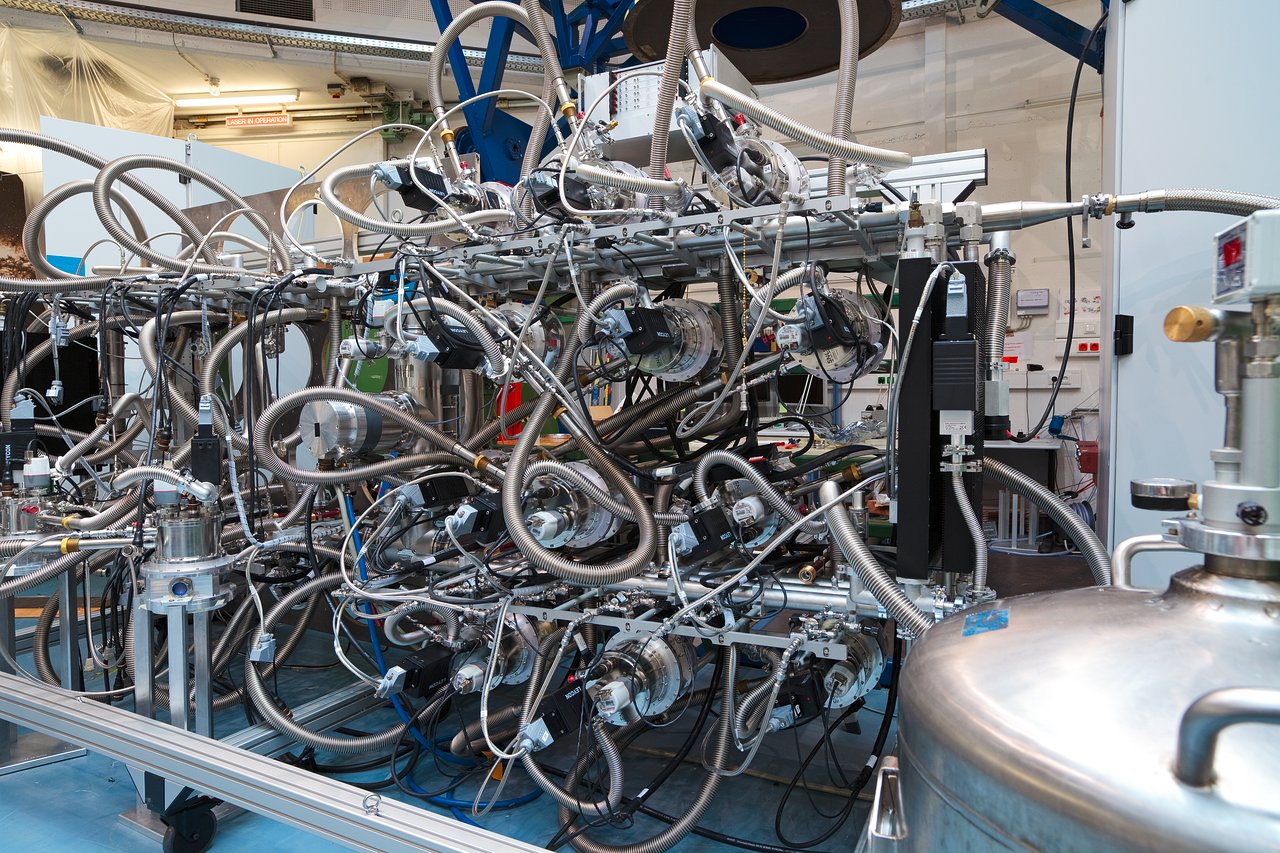

The search was on to find stars born within the Leo Ring, young and massive enough to light up the heavy elements in the surrounding gas. These stars might be so faint and sparse that the hot regions around them might have escaped detection for decades — detecting them would require a powerful instrument and telescope, such as the MUSE instrument on ESO’s VLT. Giovanni Cresci, who is also from INAF and was involved in the research recently published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, said, “We were already using MUSE and other instruments at ESO to study nearby and distant galaxies. So, when Edvige told us of the Leo Ring mystery, we realised that MUSE would be ideal to finally provide an answer about the origin of this huge structure”.

By using MUSE, the astronomers looked at three clumps of hydrogen gas where UV radiation had been found. “For the first time within the ring, we have detected nebulae ionised by rare and isolated massive stars, 30–40 times more massive than our Sun,” says Corbelli. The presence of these stars and nebulae meant the team was able to measure the abundance of heavy elements within the nebulae, which proved the stars were in the Leo Ring and suggested the gas was not primordial.

Filippo Mannucci, an astronomer at INAF-Arcetri, says, “We have been measuring chemical abundances in galaxies for many years, but we had never applied our methods to such a special object.” During their lifetimes, massive stars produce heavier and heavier elements until they reach iron, run out of fuel and explode as supernovae. Cresci expands, “Our observations allowed us to see for the first time these faint and rare little spots of gas ionised by the few young, massive stars in the ring.”

The team found a large abundance of heavy elements throughout the structure. “To pollute the ring with so many heavy elements, we would need many more stars than we observed,” says Corbelli. The lack of stars then raises more questions: how were these heavy elements dispersed throughout the structure?

Without the presence of many additional stars, the gas must have been enriched with these elements in a place where a lot of older stars are found, for example in an older galaxy.

“This means the ring is not a leftover gas cloud sitting around from the time when other galaxies were forming. The gas has been enriched by heavy elements in a galaxy disc, and later removed by the gravitational pull of a galaxy-galaxy encounter before forming the ring,” explains Corbelli.

The answer of how the Leo Ring came to be is through the collision of two galaxies. This massive energetic event spanning millions of years had such a strong gravitational force that gas, and heavy elements, were pulled from within a galaxy and dispersed throughout space. Previous work led by Leo Michel-Dansac at the University of Lyon in 2010 using computer simulations suggested that two galaxies, Messier 96 and NGC 3384, may have collided to form the Leo Ring. Corbelli's team have now confirmed that a close encounter between galaxies is the most likely scenario for the formation of this mysterious object.

This climactic solution to the Leo Ring mystery came through decades worth of research and innovation. After nearly 40 years, we finally have closure on its origin and can appreciate how existing theories were challenged and changed in the light of new evidence. However, the Leo Ring has yet to yield all of its secrets. Corbelli concludes, “Now that we have established that the gas has been removed from a galaxy during a galaxy-galaxy encounter, the big question for the future is: why did the ring not manage to form more stars?”

Numbers in this article

| 38 | The number of years between the discovery of the Leo Ring and Corbelli’s research |

| 1983 | The year the Leo Ring was initially discovered |

| 650,000 | The diameter of the Leo Ring in light-years |

Links

Biography Justin Tabbett

Justin Tabbett is a former science journalism intern at ESO. Before working at ESO, Justin completed an MSci in Physics with Industrial Experience from the University of Bristol, and spent a year working for ISIS Neutron and Muon Source and the Central Laser Facility as a Science Communicator.

Biography Emma Foxell

Emma Foxell is the former ESO blog editor, and a former science communication intern at ESO. Before this, she completed her PhD at the University of Warwick (UK) in the field of exoplanets and transit surveys, focusing on red dwarfs.